Neurodiversity

Neurodivergence and Disability: Beyond the Checkbox Trap

Is neurodivergence a disability? No, neurodivergence is not inherently a disability; rather, it describes the natural variations in human brains and cognition. However, for many individuals, neurodivergence can manifest as a disability when societal structures and environments create significant barriers and limitations to participation. The relationship between neurodivergence and disability is complex, shifting based on context, time, and the support systems available, challenging rigid categorical thinking. This guide explores the critical nuance of neurodivergence disability: beyond simplistic labels and into a deeper understanding of human experience.

Key points

- Societal norms often demand rigid categories for disability, but human experiences are inherently fluid and complex.

- Neurodivergence can present as a non-apparent disability, an apparent disability, or not a disability at all, depending on context.

- True inclusion and human flourishing come from recognizing everyone's inherent dignity, rather than fixating on restrictive labels.

Table of Contents

- Understanding Neurodivergence and Disability: A Nuanced View

- The Social Model of Disability: Shifting Perspectives

- The Real Costs of Rigid Categorization

- Navigating Legal Frameworks and Protections

- Beyond Labels: Cultivating Dignity and Inclusive Environments

Understanding Neurodivergence and Disability: A Nuanced View

People frequently grapple with defining neurodivergence, often attempting to fit it into a simple "yes" or "no" box regarding disability. However, this approach fundamentally misunderstands the rich complexity of human neurology. Neurodivergence encompasses a wide spectrum of brain differences, including autism, ADHD, dyslexia, Tourette's, and synesthesia, among others. These are not illnesses but rather variations in how brains are wired and function.

Societies, driven by administrative convenience, often push for clear-cut classifications: disabled or not disabled. This rigid categorization, however, causes significant distress and overlooks the fluidity of lived experience. The reality is far more intricate than any checklist can capture, especially when considering the dynamic interplay between an individual's neurology and their environment. The challenge of neurodivergence disability: beyond simplistic labels lies in acknowledging this inherent complexity.

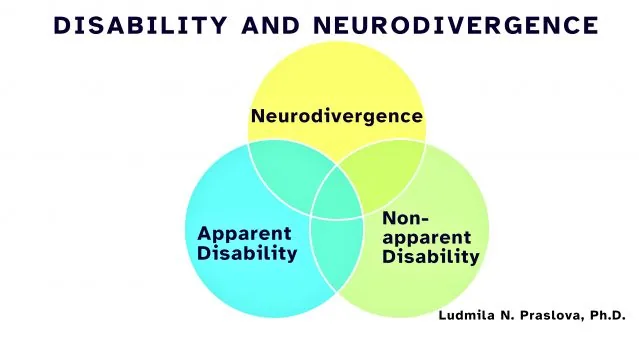

A Venn diagram illustrating the complex relationship between disability and neurodivergence. Source: Ludmila Praslova

As illustrated by the diagram above, created by Ludmila Praslova, box-focused approaches miss crucial nuances. Forcing linear categories onto a nonlinear, time- and context-dependent human reality inevitably leads to misrepresentation and pain. In practice, neurodivergence can manifest in several ways:

- Non-apparent disability: An individual with ADHD or autism might experience significant internal struggles limiting their daily participation, even if these challenges are not immediately visible to others. They may need specific supports to navigate work or social settings, yet their needs often go unrecognized or are dismissed.

- Apparent disability: Some forms of neurodivergence present with outwardly observable struggles or limitations. Examples include non-speaking autism, Tourette's syndrome with visible tics, or significant motor coordination challenges. In these cases, others more readily perceive the individual as disabled, and societal barriers become more evident.

- Not disability: Certain neurodivergent traits, such as giftedness or synesthesia, typically do not manifest as disabilities. In fact, with appropriate accommodations and supportive environments, some neurodivergent individuals--like those with well-accommodated AuDHD or dyslexia--can experience their differences as distinct advantages or "superpowers" that enhance creativity and problem-solving. This highlights the crucial role of environment in shaping the experience of neurodivergence disability: beyond inherent traits.

These categories are not fixed, discrete boxes but rather different perspectives on a single, complex phenomenon. Which perspective applies depends entirely on the specific context and moment in time, underscoring the dynamic nature of neurodivergent experiences. This understanding is critical for fostering genuine inclusion in 2025 and beyond (Harvard, 2024).

The Social Model of Disability: Shifting Perspectives

The traditional medical model often views disability as an individual's impairment, something to be 'fixed.' However, Oliver's social model of disability offers a transformative perspective. This model distinguishes between impairment, which refers to a person's physical or mental condition, and disability, which arises from societal barriers and environmental mismatches. You are not disabled because you cannot walk; you are disabled by buildings lacking ramps or public transport systems designed exclusively with stairs.

Applying this model to neurodivergence radically shifts our understanding. It suggests that individuals are not disabled by their unique brain processing, but rather by environments that demand everyone conform to an artificially narrow range of sensory processing, attention regulation, and social communication. For example, a neurodivergent person might thrive working from home, controlling their sensory input and managing their schedule. However, place them in a brightly lit, noisy open-plan office with constant interruptions and mandatory social events, and they may become distressed and functionally disabled by the environment. Their neurology hasn't changed, but the compatibility between their brain and their surroundings has dramatically deteriorated.

Consider a child with ADHD who excels at hands-on projects and learns best through movement and exploration. In a forest, they might be deeply engaged, noticing intricate patterns in leaves and following the path of ants, completely unhindered. This child is not disabled in this natural, accommodating environment. Now, imagine the same child forced into uncomfortable clothes, confined to a rigid desk, and subjected to harsh fluorescent lights and incessant buzzing in a traditional classroom setting. Here, they might become overwhelmed, experience situational mutism, or exhibit visible distress. The school environment, with its sensory overload and demand for stillness, has created a neurodivergent disability, rather than the child's inherent neurology.

Another contemporary example involves digital accessibility. A neurodivergent individual might struggle with complex, visually cluttered websites or apps that lack clear navigation and text-to-speech options. While their cognitive processing difference is the impairment, the poorly designed digital environment is what creates the disability, limiting their access to essential services or information. This highlights that both "my dyslexia is a superpower" and "my dyslexia is a disability" can be simultaneously true for the same person, depending on the context, support systems, and the design of their environment. This dynamic understanding is key to addressing neurodivergence disability: beyond just individual traits, recognizing the profound impact of societal design.

The Real Costs of Rigid Categorization

When we insist on treating apparent disability, non-apparent disability, and neurodivergence as distinct, static boxes, we inadvertently perpetuate harmful stereotypes. This rigid thinking often relies on an "overall functioning" assumption, believing that a person's ability in one area dictates their capabilities across the board. The consequences of these stereotypes are profound and often brutal, impacting access to education, employment, and basic human dignity. This is a significant challenge when addressing neurodivergence disability: beyond simple labels.

One extreme consequence is the denial of ability. This occurs when a neurodivergent individual's perceived limitation, such as limited verbal communication, is wrongly interpreted as a sign of impaired intellectual functioning. For instance, a non-speaking autistic person might be assumed to lack comprehension, agency, or sophisticated thought simply because their communication method differs. This often leads to them being denied appropriate education, autonomy in decision-making, or even the presumption of competence. They might be overlooked for roles that require analytical thinking, even if they possess exceptional skills, purely because of a single, apparent marker of disability.

Conversely, we see the denial of difficulty. This happens when an individual's strengths or achievements are used to dismiss their very real struggles. An eloquent communicator might be told they "don't seem autistic" and therefore couldn't possibly need workplace accommodations for sensory sensitivities. Similarly, someone's success in a creative field might be used as "evidence" that their ADHD isn't genuine, leading to accusations of exaggerating their needs or not trying hard enough. In a 2025 context, with increasing awareness of "masking" among neurodivergent individuals, this denial can be particularly damaging. Their non-apparent and context-specific challenges--like executive function difficulties, social exhaustion, or sensory overwhelm--are invalidated because they can "pass" as neurotypical in certain situations (Harvard, 2024).

Both forms of denial stem from a fundamental misunderstanding: the same person can possess remarkable strengths alongside apparent and non-apparent disabilities, and these can fluctuate significantly with context. Neither their abilities nor their struggles tell the complete story of their functioning. Forcing people into boxes that serve administrative ease rather than human reality denies them the full spectrum of their embodied experience, preventing genuine support and inclusion. It undermines the very essence of understanding neurodivergence disability: beyond surface-level observations.

Navigating Legal Frameworks and Protections

The inherent fluidity of neurodivergent experiences clashes directly with the rigid, static categories often demanded by legal and bureaucratic systems. While human reality is dynamic, evolving day-to-day or even hour-to-hour, legal frameworks typically require clear-cut classifications: disabled or not disabled, neurodivergent or neurotypical. This demand for static checkboxes serves administrative convenience, but frequently fails to capture the nuanced way humans function in variable contexts. The boundaries between apparent disability, non-apparent disability, and neurodivergence are not fixed; they are permeable, shifting, and deeply overlapping.

In many conditions, the experience of disability or ability can change dramatically throughout a lifespan, influenced by factors like hormonal cycles, stress levels, medication adjustments, aging, and critically, environmental design. Someone with a fluctuating neurological condition might require substantial support on a Tuesday due to sensory overload, yet function independently on Wednesday in a calmer setting. Bureaucracies, however, struggle to process this fluidity, preferring to impose rigid, linear categorization onto inherently nonlinear and dynamic phenomena.

Despite these limitations, legal protections are absolutely essential in the modern world. Legislation in countries like the U.S. (e.g., Americans with Disabilities Act) and Canada (e.g., Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act) typically defines disability as "a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities." This legal approach attempts to draw clear lines where none exist naturally, forcing the question: is someone "disabled enough" to qualify for protection and support? (Note: This is a general overview and not legal advice).

For many neurodivergent individuals, navigating this pragmatic problem requires a strategic and contextual approach. Someone with ADHD, for example, might not typically consider themselves disabled in a supportive environment. However, if a new manager creates a chaotic work setting with unclear priorities, last-minute deadlines, and micromanagement, it could overtax their executive function, substantially limiting their ability to hold a job. In this scenario, documenting what creates these substantial limitations becomes a necessary step to access legal protections and workplace accommodations. In 2025, advocates continue to push for legal frameworks that better acknowledge the dynamic and environmental aspects of neurodivergence and disability, moving beyond purely medicalized definitions to ensure broader access to rights and support.

Beyond Labels: Cultivating Dignity and Inclusive Environments

The core challenge of neurodivergence disability: beyond simple categorization is to move past the limitations of checkboxes and embrace a more holistic view of human experience. When we compel individuals to choose a single label--disabled or not, neurodivergent or not--we force them to flatten the rich complexity of their embodied reality. These artificial categories, designed for institutional ease, are then often misused to deny people the acknowledgement of either their unique abilities or their very real struggles. The alternative is not simply to create more categories, but to foster environments built on dignity, flexibility, and universal design for all humans.

The conversation must evolve beyond merely labeling someone as "disabled" or "neurodivergent." The true work lies in proactively designing systems, workplaces, schools, and communities that empower everyone to thrive, regardless of where they might land on a Venn diagram or within legal definitions. This shift requires a fundamental change in perspective, moving from reactive accommodations to proactive inclusion. In 2025, a growing emphasis on inclusive design principles is reshaping how we approach environments and interactions.

Consider the distinct, yet interconnected, concepts that guide this approach:

- Accommodations: These are short-term, specific adjustments designed to remove barriers for an individual in a particular context. For example, providing noise-canceling headphones for an autistic student in a noisy classroom, or allowing a dyslexic employee to use specialized text-to-speech software. While essential, accommodations are often reactive and individualized, addressing symptoms rather than root causes of inaccessibility.

- Accessibility: This refers to thoughtful, proactive design that removes barriers for everyone, regardless of disability or neurotype. An accessible environment is inherently inclusive. Examples include creating digital platforms with clear navigation, multiple input options, and customizable visual settings (e.g., font size, color contrast), which benefit not just individuals with visual impairments or dyslexia, but also those with cognitive differences or temporary situational limitations. Similarly, universal design principles in architecture, such as ramps and automatic doors, benefit parents with strollers, delivery personnel, and wheelchair users alike.

- Inclusion: This represents the deepest level of change: a fundamental culture shift. It involves building workplaces, educational institutions, and communities where asking for help is seen not as a weakness but as a natural part of human interaction. It's a culture where everyone is protected, respected, and valued for their unique contributions. Inclusion means that being different does not require constant justification of one's existence or abilities. It's about creating environments where neurodivergent individuals feel a sense of belonging and psychological safety, empowering them to bring their full selves to every space. This comprehensive approach ensures humanity wins, fostering a world where dignity is paramount.

Conclusion

The journey to understanding neurodivergence and disability is far more complex than simple checkboxes allow. As we've explored, neurodivergence is a natural variation of the human brain, but it can become a disability when societal structures and environments create significant barriers. The social model of disability highlights that it is often the mismatch between an individual's neurology and their surroundings that creates limitations, not the neurology itself. The cost of rigid categorization is high, leading to the denial of both abilities and genuine struggles.

Moving forward in 2025 and beyond, the imperative is clear: we must shift our focus from labeling individuals to designing systems that cultivate dignity and flexibility for all. While legal frameworks provide crucial protections, they are imperfect tools that require strategic navigation. The ultimate goal is to transcend mere accommodations, striving for true accessibility and fostering cultures of inclusion where every person is valued, protected, and empowered to thrive. By embracing this holistic perspective on neurodivergence disability: beyond limiting definitions, we build a more equitable and compassionate world for everyone.