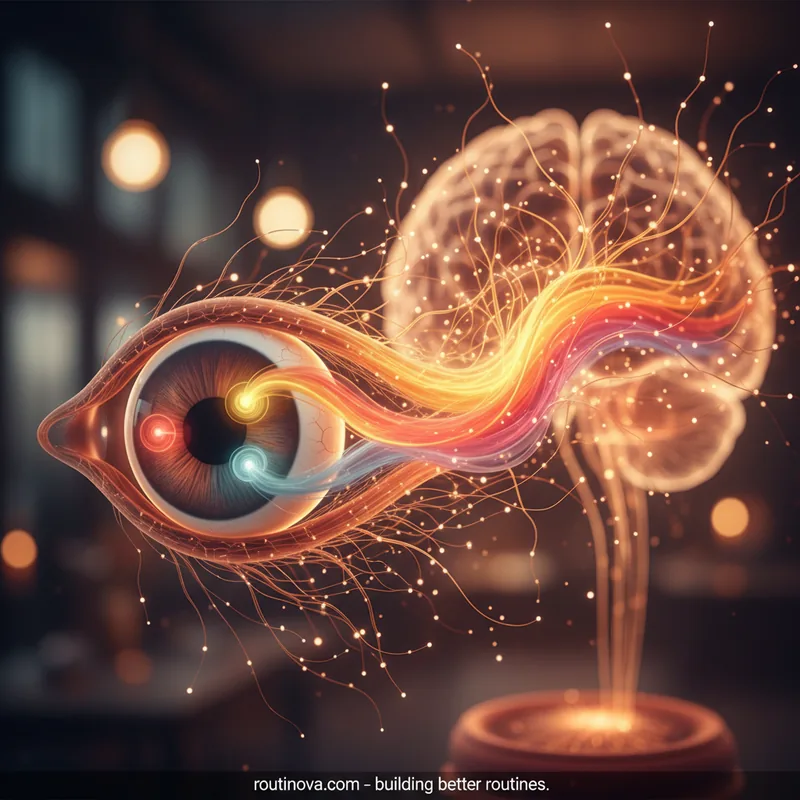

Have you ever paused to wonder how your brain transforms light waves into the vibrant tapestry of colors you see every day? If you've ever been captivated by a sunset or marvelled at a rainbow, you're experiencing a complex biological process that scientists have sought to understand for centuries. The fascinating answer lies in an early theory that explains how we perceive color: the trichromatic theory of color vision. This foundational concept suggests that our eyes possess three distinct types of receptors, each finely tuned to detect specific wavelengths of light--red, green, and blue--and it's their combined signals that allow us to discern millions of different hues.

The Mechanics of Color Perception

Our ability to see color begins within the retina, a light-sensitive layer at the back of the eye. Here, millions of specialized cells known as photoreceptors diligently capture incoming light. These photoreceptors are categorized into two main types: rods and cones. Rods excel in low-light conditions, helping us navigate in dim environments, but they don't contribute to color perception. Cones, on the other hand, are the true artists of our visual system, responsible for detecting color and fine details in normal lighting (Harvard Medical School, 2024).

The trichromatic theory, also known as the Young-Helmholtz theory, posits that these cones are not all alike. Instead, they come in three varieties, each preferentially sensitive to different wavelengths of the visible light spectrum. One type is most responsive to short wavelengths, which we perceive as blue. Another is sensitive to medium wavelengths, seen as green, and the third responds best to long wavelengths, which we interpret as red. It's the intricate interplay and varying stimulation levels of these three cone types that allow our brains to construct the vast spectrum of colors we experience. For instance, seeing yellow involves both red and green cones being stimulated simultaneously, while purple results from blue and red cone activation (NIH, 2024).

With three functional cone types, the average human eye can distinguish an astonishing one million different colors. This rich visual experience is a testament to the efficiency of this early theory that explains the intricate dance between light and biology.

Tracing the Origins of Trichromatic Theory

The concept of color perception has long fascinated scientists and philosophers alike. Among the earliest and most influential explanations is the trichromatic theory, a groundbreaking idea championed by two renowned researchers: Thomas Young and Hermann von Helmholtz. Young, an English physician and physicist, first proposed in 1802 that the eye needed only three types of receptors to perceive all colors. He based this assertion on the observation that combining just three primary colors in varying proportions could generate every other color in the visible spectrum--a concept familiar to artists who mix pigments (Young, 1802). Think of how a painter mixes red, yellow, and blue to create a myriad of shades; Young applied a similar logic to how our eyes might work with light.

Decades later, in the mid-1800s, the German physicist and physician Hermann von Helmholtz significantly expanded upon Young's initial hypothesis. Helmholtz refined the idea by proposing that the three types of photoreceptors were specifically sensitive to short (blue), medium (green), and long (red) wavelengths of light. He further suggested that the brain interprets color by assessing the relative strength of signals received from each of these receptor cells simultaneously. Through meticulous experiments, Helmholtz demonstrated that individuals with normal color vision required precisely three distinct photoreceptors, each tuned to one of these primary wavelengths, to perceive the full spectrum of visible colors (Helmholtz, 1867). His work cemented this early theory that explains the biological basis of color vision, leading to its enduring recognition as the Young-Helmholtz theory.

These early investigations laid the groundwork for understanding how our visual system translates the physical properties of light into our subjective experience of color. It's truly a foundational early theory that explains one of our most fundamental senses.

The Specialized Cone Receptors

While Young and Helmholtz theorized about three types of color receptors, their actual identification took many more decades. It wasn't until much later that researchers pinpointed the specific pigments (opsins) within the cones responsible for absorbing different light waves. These discoveries confirmed the trichromatic model, categorizing the cones based on their peak sensitivity:

- S-cones (Short-wavelength cones): Most sensitive to blue light.

- M-cones (Medium-wavelength cones): Most sensitive to green light.

- L-cones (Long-wavelength cones): Most sensitive to red light.

The human visual system can perceive wavelengths ranging from approximately 400 nanometers (violet) to 700 nanometers (red). The familiar mnemonic ROY G BIV (Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo, Violet) represents the full spectrum of visible light. Each cone type exhibits varying levels of sensitivity; for instance, S-cones (blue) are generally the most sensitive, while L-cones (red) are often the least responsive. The brain's remarkable ability to compare the input from these different cones allows it to precisely interpret the color of any light source, much like how the tiny red, green, and blue pixels on your digital screen combine to create every color you see (Mayo Clinic, 2024).

Most individuals possess normal trichromatic vision, meaning they have all three types of functioning cones. However, a rare genetic mutation can lead to tetrachromatic vision in some women, endowing them with a fourth type of cone. This extraordinary ability allows them to perceive exponentially more colors than the average person, potentially hundreds of millions of distinct hues, illustrating the incredible potential diversity of human perception (Jordan et al., 2010).

Understanding Color Blindness

A discussion of color vision wouldn't be complete without addressing color blindness, a condition that highlights the critical role of our cone receptors. The primary cause of color blindness is a genetic alteration in one or more of the cone pigments, leading to a reduced or absent ability to differentiate certain colors. This condition serves as a compelling demonstration of the early theory that explains color perception by showing what happens when the system is incomplete.

The most common forms of color blindness involve difficulty distinguishing between reds and greens. This typically occurs due to a deficiency or mutation in the M-cones (green) or L-cones (red), or both, which decreases their sensitivity to green or red wavelengths, respectively. For example, someone with deuteranomaly (a common type of red-green color blindness) might struggle to differentiate between ripe strawberries and their green leaves, or to correctly identify the red and green lights on a traffic signal. Less common is blue-yellow color blindness, which stems from issues with S-cones and results in difficulty discerning blues from greens, or reds from yellows (American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2023).

In extremely rare cases, individuals may lack all three types of cone pigments, resulting in monochromatic vision. For these individuals, the world appears in shades of gray, similar to an old black-and-white photograph. This spectrum of color perception underscores the vital contribution of each cone type:

- Monochromatic: Approximately 500 shades of gray.

- Dichromatic: Around 10,000 colors.

- Trichromatic: Up to 1 million colors.

- Tetrachromatic: Potentially 100 million colors.

Trichromatic Theory and the Opponent-Process Model

For a time, the trichromatic theory was often seen as competing with another significant explanation for color vision: the opponent-process theory. Developed by Ewald Hering, this theory proposes that color perception is controlled by three opposing receptor systems: red-green, blue-yellow, and black-white. For example, when you stare at a red object for a long time and then look away, you might see a green afterimage--this is explained by the fatigue of the red receptors in the red-green system, causing the green system to overcompensate.

However, modern understanding recognizes that these two theories are not mutually exclusive but rather describe different stages of color processing within the visual system. The trichromatic theory, this early theory that explains, accurately describes color vision at the receptor level, focusing on how cones in the retina initially detect light wavelengths. The opponent-process theory, on the other hand, describes color vision at the neural level, explaining how signals from the cones are processed further up in the visual pathway, after they leave the retina and travel towards the brain (Shevell & Martin, 2017). Together, these two theories provide a more comprehensive understanding of the remarkable journey light takes from our eyes to our brains, culminating in the rich and vivid experience of color.