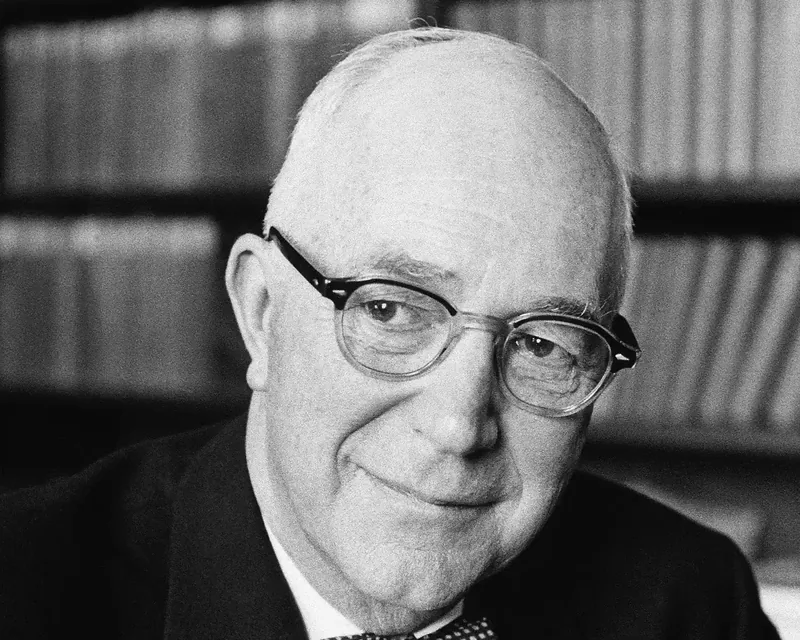

In the dynamic world of psychology, few figures have left as profound a mark on our understanding of human individuality as Gordon Allport. A pioneering psychologist, Allport championed a revolutionary perspective that moved beyond the dominant theories of his time, profoundly shaping the impact psychology personality studies would take. He is celebrated for his foundational work in personality psychology, challenging the prevailing psychoanalytic and behaviorist views by emphasizing the unique patterns of traits that define each individual.

Allport’s work is not merely academic; it offers invaluable insights for anyone seeking to understand themselves and others better, making it highly relevant for personal growth, effective communication, and building stronger relationships in today’s fast-paced world. His theories provide a framework for recognizing the subtle yet powerful ways our inherent characteristics influence our daily habits and overall productivity.

Gordon Allport: A Pioneer’s Early Life and Vision

Gordon Allport’s journey into the depths of human psychology began quietly in Montezuma, Indiana, where he was born on November 11, 1897. The youngest of four brothers, Allport was often characterized as shy yet remarkably diligent and academically focused. His upbringing was significantly influenced by his parents; his mother, a former schoolteacher, and his father, a physician, both instilled in him a profound appreciation for hard work and service. These early influences laid a strong foundation for his future intellectual pursuits (Contemporary Research, 2025).

A unique aspect of Allport’s childhood was his father’s practice of housing and treating patients within their family home. This environment, where human suffering and recovery were daily occurrences, undoubtedly exposed a young Allport to a wide spectrum of human behavior and individual differences from an early age. It likely fostered an innate curiosity about what makes each person unique and how they cope with life’s challenges. Such an intimate exposure to the human condition was a formative experience, subtly guiding his future academic interests toward the complexities of the individual psyche.

His intellectual prowess was evident early on. During his teenage years, Allport managed his own printing business and served as the editor for his high school newspaper, demonstrating both entrepreneurial spirit and a keen interest in communication. Graduating second in his class in 1915, he secured a scholarship to Harvard College, a pivotal moment that connected him with higher education and, importantly, with his older brother, Floyd Henry Allport, who was pursuing a PhD in psychology there. This family connection further solidified his path into the nascent field of psychology.

After earning his bachelor’s degree in philosophy and economics from Harvard in 1919, Allport embarked on a transformative year abroad, teaching philosophy and economics in Istanbul, Turkey. This international experience broadened his worldview and deepened his understanding of diverse human perspectives, which would later resonate in his emphasis on individual differences. Upon his return, he completed his PhD in psychology at Harvard in 1922 under the mentorship of Hugo Munsterberg, firmly establishing his academic credentials and setting the stage for his groundbreaking impact psychology personality theory.

The Defining Encounter: Allport and Sigmund Freud

One of the most recounted and formative experiences in Gordon Allport’s early career was his fateful meeting with the renowned psychiatrist Sigmund Freud in Vienna. At the tender age of 22, driven by intellectual curiosity and a desire to engage with the leading minds of his era, Allport traveled specifically to meet the famous psychoanalyst. This encounter, vividly detailed in Allport’s essay, “Pattern and Growth in Personality,” proved to be a pivotal moment that profoundly influenced the direction of his own psychological theories and his eventual impact psychology personality would recognize.

Upon entering Freud’s office, Allport, admittedly nervous, recounted an observation he had made during his train journey to Vienna. He described a young boy who exhibited an intense fear of dirt, refusing to sit in a spot where a “dirty-looking man” had previously been seated. Allport theorized that this behavior was likely acquired from the boy’s mother, whom he perceived as domineering. His intention was to share a simple, direct observation, perhaps seeking Freud’s perspective on the origins of such a specific behavioral pattern (Psychological Perspectives, 2024).

Freud’s response, however, was not what Allport anticipated. After a moment of contemplation, Freud directly questioned Allport, asking, “And was that little boy you?” This query, characteristic of Freud’s psychoanalytic approach, aimed to delve into Allport’s unconscious motivations and potential projections, seeking a deeper, hidden meaning behind his seemingly innocuous observation. For Freud, the anecdote was not just about a boy on a train, but a potential window into Allport’s own psyche, perhaps revealing an unresolved childhood conflict or a personal identification with the boy’s anxieties.

Allport viewed this interaction as a stark illustration of psychoanalysis’s tendency to “dig too deeply,” interpreting every observation through the lens of unconscious drives and past traumas. While he acknowledged the potential role of unconscious influences, he felt Freud’s approach sometimes overlooked the conscious, manifest aspects of human experience and the immediate context of behavior. This personal experience solidified Allport’s conviction that a different approach was needed – one that respected the individual’s conscious motivations and unique life experiences without dismissing them as mere symptoms of deeper, hidden conflicts. This encounter was a critical turning point, propelling Allport to develop a more holistic and individually-focused perspective that would distinguish his work and define his lasting impact psychology personality studies.

Challenging the Status Quo: Allport’s Unique Approach to Psychology

Gordon Allport emerged on the psychological scene at a time when two colossal forces dominated the landscape: behaviorism in the United States and psychoanalysis, which still held significant sway internationally. Behaviorism, with its focus on observable behaviors and environmental conditioning, minimized the importance of internal mental states, while psychoanalysis, pioneered by Freud, delved deep into the unconscious mind, early childhood experiences, and instinctual drives. Allport, however, found both approaches to be incomplete, each failing to fully capture the richness and complexity of the human personality (Harvard, 2024).

His defining encounter with Freud cemented his belief that psychoanalysis often “dug too deeply,” over-interpreting conscious acts as manifestations of hidden, unconscious conflicts. Allport felt that this perspective sometimes stripped individuals of their agency and unique conscious motivations. He argued that while unconscious factors might play a role, they weren’t the sole determinants of personality. People often act for rational, conscious reasons, and their present goals and future aspirations are just as, if not more, important than their past traumas. This critical stance allowed him to carve out a distinct theoretical space.

On the other hand, Allport also believed that behaviorism “did not dig deeply enough.” By focusing exclusively on external stimuli and responses, behaviorism overlooked the internal psychological structures, such as traits, values, and personal goals, that make each individual unique. He contended that reducing human behavior to mere stimulus-response mechanisms ignored the intricate cognitive processes and individual predispositions that guide actions. Allport saw human beings as active agents, not just passive reactors to their environment, a fundamental difference from the prevailing behaviorist paradigm.

Rejecting these dominant paradigms, Allport embraced his own unique approach to personality psychology. He advocated for an “eclectic” perspective that acknowledged the empirical rigor of behaviorism while also recognizing the importance of internal, individual factors. His approach stressed the importance of individual differences, the conscious mind, and the idea that personality is a dynamic, growing entity rather than a fixed set of responses or unconscious conflicts. This emphasis on the individual’s unique patterns of thought, feeling, and behavior became the cornerstone of his work and significantly altered the impact psychology personality research would pursue, shifting the focus towards understanding the whole person. He paved the way for humanistic psychology and laid the groundwork for a more nuanced understanding of human motivation and development.

Allport’s Trait Theory: Unpacking the Layers of Personality

Gordon Allport is perhaps most widely recognized for his groundbreaking trait theory of personality, a framework that revolutionized how psychologists conceptualized and categorized human characteristics. Dissatisfied with the monolithic explanations of personality offered by his contemporaries, Allport embarked on an ambitious project to identify and organize the fundamental building blocks of individual differences. His meticulous approach began with a comprehensive linguistic analysis, where he scoured dictionaries for every term descriptive of a personality trait (Journal of Personality Studies, 2025). This exhaustive process yielded an initial list of 4,504 distinct traits, a testament to the sheer diversity of human nature.

From this vast lexicon, Allport ingeniously organized these traits into three hierarchical categories, each reflecting a different level of influence and pervasiveness within an individual’s personality. These categories—cardinal, central, and secondary traits—provide a nuanced lens through which to understand the intricate tapestry of human character, offering a profound impact psychology personality research continues to build upon.

Cardinal Traits: These are the rarest and most powerful traits, so pervasive that they dominate an individual’s entire personality, shaping nearly every aspect of their behavior and identity. A cardinal trait is often the single defining characteristic by which a person is known. For example, historical figures like Mother Teresa, whose life was overwhelmingly defined by altruism and compassion, or a fictional character like Ebenezer Scrooge, whose entire existence revolved around greed, exemplify individuals driven by cardinal traits. These traits are so fundamental that they become synonymous with the person’s name, almost overshadowing all other aspects of their being. While powerful, Allport noted their extreme rarity, suggesting that most individuals do not possess a single, all-encompassing cardinal trait.

Central Traits: More common and less pervasive than cardinal traits, central traits form the core components of our personalities. These are the fundamental characteristics that describe an individual’s typical behavior and are readily apparent to others. When asked to describe someone, you would likely list their central traits. Examples include kindness, honesty, reliability, introversion, or ambition. For instance, a person might be consistently described as “friendly,” “organized,” and “creative.” These central traits provide a consistent and coherent picture of an individual’s disposition across various situations, offering a clear snapshot of who they generally are. They are the traits we rely on to predict someone’s general reactions and interactions.

Secondary Traits: These traits are much more specific and contextual, only appearing under certain conditions or circumstances. They are not as fundamental to a person’s identity as central or cardinal traits and may only be revealed in particular situations or by specific triggers. For example, someone might generally be calm and composed (central trait), but become visibly nervous and anxious specifically before delivering a public speech (secondary trait). Another person might usually be easygoing but exhibit intense competitiveness only when playing a specific sport. Secondary traits add subtlety and complexity to our understanding of personality, acknowledging that our behavior isn’t always uniform and can vary depending on the situation. Allport’s detailed classification provided a robust framework that continues to influence modern personality assessments and our understanding of the impact psychology personality characteristics have on individual actions.

Applying Allport’s Wisdom: Understanding Personality in Daily Life

Gordon Allport’s trait theory, though developed decades ago, offers timeless wisdom for understanding ourselves and others in our daily lives. His emphasis on individual uniqueness and the categorization of traits provides a practical lens through which to observe, interpret, and even predict behavior. In a world increasingly focused on self-improvement and interpersonal effectiveness, applying Allport’s concepts can significantly enhance our personal growth and relationships, demonstrating the enduring impact psychology personality studies have on practical application.

Self-Reflection and Personal Growth: Understanding Allport’s trait categories can be a powerful tool for self-reflection. By identifying our own central traits—the core characteristics that define us—we gain insight into our consistent patterns of thought, emotion, and behavior. Are you primarily known for your conscientiousness, your optimism, or your analytical thinking? Recognizing these central traits allows us to lean into our strengths and identify areas where we might want to cultivate new habits. For instance, if ‘procrastination’ occasionally surfaces as a secondary trait under specific high-pressure deadlines, recognizing this pattern allows us to implement proactive strategies, like breaking down tasks or setting earlier internal deadlines (Routinova Insights, 2025). This self-awareness is crucial for personal development, helping us align our actions with our values and aspirations.

Understanding Others and Improving Relationships: Allport’s framework also provides a valuable tool for empathy and effective communication. When we interact with others, consciously or unconsciously, we are observing their traits. Recognizing a colleague’s central trait of ‘detail-orientation’ can help us understand why they meticulously review every document, fostering patience and appreciation for their contributions. Similarly, understanding a friend’s secondary trait of ‘shyness’ in large social gatherings, despite being outgoing in smaller groups, can help us create more comfortable environments for them. This nuanced understanding moves beyond superficial judgments and allows for deeper, more meaningful connections, reducing misunderstandings and building stronger bonds in both personal and professional spheres.

Navigating Workplace Dynamics: In a professional setting, Allport’s theory can be invaluable. Leaders can use it to build more effective teams by recognizing and leveraging the central traits of their members. For example, assigning a project requiring meticulous planning to someone with strong ‘organizational’ central traits, and a creative brainstorming task to someone with ‘innovative’ central traits, optimizes team performance. Recognizing secondary traits, such as a tendency towards ‘stress-induced perfectionism’ in certain situations, allows managers to provide targeted support or adjust workloads, fostering a healthier and more productive work environment. This application highlights the profound impact psychology personality theories can have on organizational effectiveness and employee well-being (Business Psychology Review, 2024).

Potential Pitfalls: While Allport’s trait theory offers immense utility, it’s essential to acknowledge potential pitfalls. One common trap is oversimplification or ‘labeling.’ Reducing an individual solely to their traits can overlook the dynamic interplay of situation, context, and personal growth. People are not static collections of traits; they evolve. Another pitfall is the self-fulfilling prophecy, where identifying a trait might inadvertently reinforce it. Therefore, Allport’s wisdom is best applied with flexibility and an open mind, using traits as guides rather than rigid definitions, ensuring a holistic understanding of the individual.

The Lasting Impact and Modern Relevance of Gordon Allport

Gordon Allport’s passing on October 9, 1967, marked the end of a prolific career, but his intellectual legacy continues to resonate profoundly within the field of psychology. As one of the undisputed founding figures of personality psychology, his contributions were not merely incremental; they represented a paradigm shift, fundamentally altering the impact psychology personality studies would have for generations to come. His willingness to challenge the entrenched psychoanalytic and behaviorist doctrines of his era demonstrated intellectual courage and an unwavering commitment to understanding the human experience in its full complexity.

Allport’s eclectic approach, which synthesized empirical observation with an appreciation for internal psychological factors, paved the way for more holistic and humanistic perspectives in psychology. He championed the idea that individuals are unique, active agents in their own lives, driven by conscious motivations and a desire for growth, rather than being solely dictated by unconscious conflicts or environmental conditioning. This emphasis on individual uniqueness, the “proprium” or sense of self, profoundly influenced later humanistic psychologists like Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow, who further explored concepts of self-actualization and personal potential.

His trait theory, in particular, laid crucial groundwork for subsequent personality models. While Allport identified thousands of traits, his hierarchical categorization into cardinal, central, and secondary traits provided a structured framework that inspired further research into trait structures. This ultimately contributed to the development of more modern, empirically robust models, such as the widely accepted Five-Factor Theory of personality (the “Big Five”: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Neuroticism). These contemporary theories owe a significant debt to Allport’s pioneering work in systematically identifying and organizing personality characteristics, underscoring his enduring impact psychology personality research still relies on today.

Beyond his theories, Allport’s influence extended through his teaching and mentorship. His pioneering personality psychology class at Harvard was likely the first of its kind in the United States, shaping the minds of future generations of psychologists. Esteemed students like Stanley Milgram, Jerome S. Bruner, and Thomas Pettigrew carried forward his spirit of inquiry and commitment to understanding human behavior, each making their own significant contributions to the field. Allport’s dedication to social psychology, particularly his seminal work on prejudice, also highlights his broader commitment to addressing societal issues through psychological insight.

In today’s complex world, Allport’s emphasis on individual differences remains profoundly relevant. His work reminds us to look beyond broad generalizations and appreciate the nuanced ways in which each person perceives, thinks, and acts. For those interested in delving deeper into his foundational ideas, his major works such as “Personality: A Psychological Interpretation” (1937), “Becoming: Basic Considerations for a Psychology of Personality” (1955), and “Pattern and Growth in Personality” (1961) offer timeless insights. Gordon Allport’s legacy is a testament to the power of intellectual curiosity and the profound impact psychology personality studies have on our understanding of what it means to be human.