Have you ever wondered what truly propels our actions, from the simplest task of grabbing a glass of water to pursuing complex life goals? Understanding human motivation is a cornerstone of psychology, and one of the earliest comprehensive attempts to explain human motivation was the Drive Reduction Theory. This foundational concept, popularized in the mid-20th century, posits that our behaviors are largely driven by the need to alleviate uncomfortable internal states, known as “drives,” which arise from physiological imbalances. Essentially, when our body signals a need – be it hunger, thirst, or warmth – we are motivated to act in ways that restore balance, bringing us back to a comfortable state of equilibrium.

1. The Foundation of Drive Reduction Theory

Drive Reduction Theory, primarily developed by behaviorist Clark Hull in the 1940s and 1950s, offered a compelling framework to explain human motivation by focusing on our biological imperative for survival. At its heart lies the concept of homeostasis, a term borrowed from physiology, which describes the body’s innate ability to maintain a stable internal environment. Think of your body as constantly striving for a perfect balance – regulating temperature, blood sugar, and hydration levels, among others. When this balance is disrupted, a state of tension or arousal, which Hull termed a “drive,” is created.

These primary drives stem directly from our fundamental biological needs. For instance, if your body temperature drops too low, you experience a “cold drive.” If your energy reserves are depleted, you feel a “hunger drive.” These drives are inherently unpleasant, acting as internal alarms that signal a physiological deficit. The discomfort serves as a powerful motivator, compelling us to engage in specific behaviors designed to reduce that tension and restore equilibrium. For example, feeling a persistent itch after a long day of outdoor activities creates a drive that motivates us to scratch, providing immediate relief and restoring comfort. This simple yet profound idea provides a clear answer to how biological needs explain human motivation.

Hull’s work was deeply influenced by earlier thinkers like Charles Darwin, Ivan Pavlov, and John B. Watson, integrating principles of evolution and learned behavior. He believed that understanding these basic physiological mechanisms was key to unlocking the mysteries of all behavior. While the theory focused heavily on biological needs, its initial widespread acceptance highlighted the intuitive appeal of explaining motivation through the lens of internal discomfort and the pursuit of relief. This emphasis on maintaining a steady state remains a core concept in many areas of biology and psychology today, informing our understanding of basic regulatory processes (Harvard, 2024).

2. Conditioning, Reinforcement, and Drive Reduction

A crucial aspect of Clark Hull’s Drive Reduction Theory, and what marked him as a neo-behaviorist, was its strong emphasis on conditioning and reinforcement. Hull proposed that the act of reducing a drive serves as a powerful reinforcer for the behavior that led to that reduction. This means that if a particular action successfully alleviates a drive, we are more likely to repeat that action when faced with the same drive in the future. This mechanism provides a clear behavioral explanation for how we learn to satisfy our needs.

Consider a scenario where you’re extremely thirsty (a strong drive). You search for water, find a faucet, and drink. The immediate relief from thirst acts as a positive reinforcement for the entire sequence of actions – searching, finding, and drinking. The next time you feel thirsty, you’ll be more inclined to repeat those same behaviors, or similar ones, because they have been “stamped in” as effective solutions. This continuous cycle of need, action, and relief is fundamental to how we adapt and survive in our environment.

Hull conceptualized this process within a stimulus-response (S-R) framework. When a specific stimulus (like the sensation of hunger) is followed by a response (eating) that leads to a reduction in the need, the connection between that stimulus and response is strengthened. This increased likelihood of the response occurring again demonstrates how learning is intrinsically tied to the reduction of physiological tension. For instance, a baby learns to cry to signal hunger; when fed, the hunger drive is reduced, reinforcing the crying behavior. This elegant interplay of drives, behaviors, and reinforcement helps to explain human motivation in a practical, observable way, demonstrating how organisms acquire behaviors essential for their survival and well-being.

3. Hull’s Ambitious Mathematical Framework

Clark Hull’s ambition extended beyond merely describing the principles of motivation; he sought to quantify them. He aimed to develop a comprehensive, mathematical theory of behavior, a “formula” that could precisely predict and explain human motivation. This was a groundbreaking and highly influential endeavor for its time, reflecting a desire to bring scientific rigor and predictability to the study of psychology, much like physics or chemistry. His famous equation, though complex and now largely historical, represented an attempt to integrate various factors influencing an organism’s likelihood to respond to a stimulus.

The formula incorporated elements such as drive strength (D), habit strength (sHr), incentive motivation (K), and even reactive inhibition (Ir, representing fatigue). Each variable was meant to represent a measurable aspect of an organism’s internal state or learned history, contributing to the overall “excitatory potential” (sEr) – the probability of a specific response occurring. While the full mathematical expression is no longer a central part of contemporary psychology, its very existence highlights Hull’s pioneering effort to create a grand, unified theory capable of explaining all behavior through a deterministic lens.

Despite its innovative spirit, this highly detailed and quantitative approach ultimately proved to be one of the theory’s weaknesses. The sheer complexity of the formula, combined with the difficulty of precisely measuring each variable in real-world scenarios, made it challenging to apply universally. Critics found it overly rigid and unable to account for the nuanced and often unpredictable nature of human actions. However, Hull’s commitment to creating a testable, scientific model significantly influenced subsequent generations of psychologists, pushing them to develop more empirically sound and comprehensive theories. His work, therefore, remains an important historical marker in the journey to explain human motivation with scientific precision, even if his specific mathematical model eventually faded from prominence.

4. Key Criticisms: Beyond Basic Physiological Needs

While Drive Reduction Theory offered a compelling initial explanation for many basic behaviors, it faced significant criticism for its limited scope, particularly when trying to explain human motivation in its entirety. One of the primary shortcomings was its struggle to account for behaviors that are not directly aimed at reducing a physiological drive. The theory excelled at explaining why we eat when hungry or drink when thirsty, but what about the myriad other motivations that guide human life?

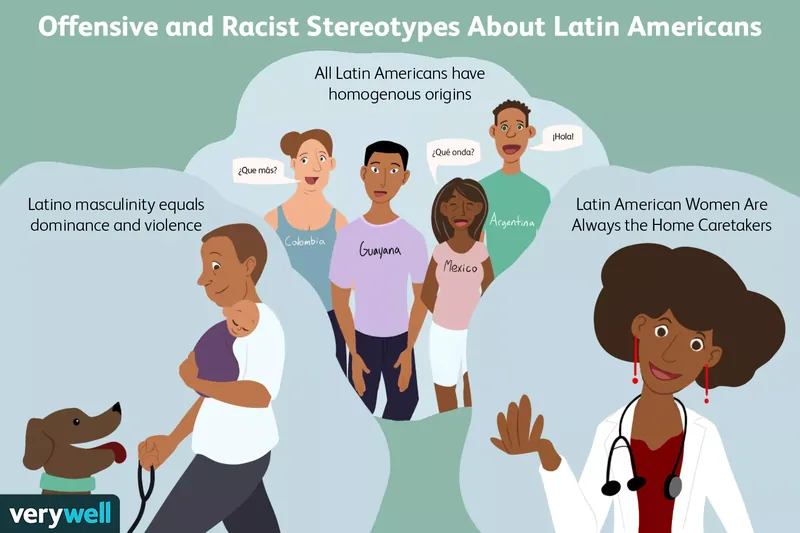

A major challenge came from the concept of secondary reinforcers. Unlike primary reinforcers (like food or water) which directly reduce biological needs, secondary reinforcers (such as money, praise, or good grades) do not. Yet, these abstract rewards are incredibly powerful motivators in human society. Money, for example, doesn’t directly quench thirst, but it allows us to acquire things that do. Drive Reduction Theory struggled to adequately explain why individuals would exert immense effort to accumulate money, given its indirect role in drive reduction. This highlighted a significant gap in its ability to encompass the full spectrum of human desires and goals.

Furthermore, the theory failed to explain behaviors that increase tension or appear to have no direct link to biological needs. Why do people engage in thrilling activities like skydiving, bungee jumping, or exploring new, challenging hobbies? These activities often induce heightened arousal and even a sense of danger, which runs contrary to the idea of reducing an unpleasant state. Similarly, why might someone eat a delicious dessert after a satisfying meal, even when they are no longer hungry? Or why do individuals pursue knowledge for its own sake, without any immediate physiological reward? These complex, intrinsically motivated behaviors, alongside actions driven by curiosity or the pursuit of novelty, demonstrated that human motivation is far more intricate than simply seeking to restore physiological balance. This inability to generalize beyond basic survival instincts ultimately limited Drive Reduction Theory’s power to fully explain human motivation.

5. The Lasting Influence and Modern Perspective

Despite the criticisms and its eventual decline in prominence, Clark Hull’s Drive Reduction Theory undeniably carved out an important place in the history of psychology. Its rigorous, scientific approach to understanding motivation, even with its limitations, set a precedent for future research. While the specific mathematical formulations are no longer widely used, the core concept of drives stemming from physiological needs continues to influence how we understand basic human regulatory processes. It forced psychologists to think systematically about what motivates us and how these motivators interact with learned behaviors.

In a 2025 context, while we acknowledge the complexity beyond simple drive reduction, the theory provides a valuable historical lens. It helps us appreciate the evolution of motivational thought, illustrating how early attempts to explain human motivation laid crucial groundwork. Modern understanding of well-being, for instance, still recognizes the fundamental importance of addressing basic physiological needs – adequate sleep, nutrition, and hydration – as foundational for overall health and cognitive function. When these basic drives are consistently unmet, it profoundly impacts an individual’s ability to engage with higher-level motivations.

The theory’s emphasis on homeostasis, the body’s internal balancing act, remains a cornerstone in fields like neurobiology and behavioral medicine. Understanding how our bodies strive for equilibrium informs treatments for conditions ranging from diabetes to addiction, where dysregulation of internal states plays a significant role. Therefore, while Drive Reduction Theory may not offer a complete picture of why we do everything we do, it serves as a powerful reminder of the deep biological roots of our most fundamental motivations. It encourages us to consider how our intrinsic physiological needs continue to shape our daily decisions and overall lifestyle, even in an era of complex psychological theories (Harvard, 2024).

6. Exploring Alternative Theories of Motivation

The limitations of Drive Reduction Theory in comprehensively explaining human motivation paved the way for the emergence of numerous alternative and more nuanced models. These newer theories sought to address the complexities of human behavior, including those not directly tied to physiological needs or drive reduction. Understanding these alternatives provides a richer, more complete picture of what truly motivates us in our daily lives.

One significant alternative is Arousal Theory, which suggests that individuals are motivated to maintain an optimal level of physiological arousal. Unlike drive reduction, which seeks to reduce tension, arousal theory proposes that we actively seek out activities that either increase or decrease our arousal to reach a preferred state. For some, this might mean seeking thrilling experiences like rock climbing, while for others, it might involve calming activities like meditation. This theory better explains why people might pursue activities that create excitement rather than simply alleviate discomfort.

Another influential model is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. This theory proposes that human motivation is structured in a hierarchy, starting with basic physiological needs (like those addressed by Drive Reduction Theory) and progressing to safety, love/belonging, esteem, and finally, self-actualization. Maslow argued that lower-level needs must be met before individuals are motivated to pursue higher-level psychological needs. This provides a much broader framework to explain human motivation, acknowledging both biological imperatives and aspirations for personal growth and fulfillment.

Furthermore, Incentive Theory highlights the role of external rewards and punishments in shaping behavior. This theory suggests that we are often motivated by the pull of desirable outcomes (incentives) rather than solely by internal pushes (drives). For example, studying for a good grade or working extra hours for a bonus are behaviors driven by external incentives. Lastly, Self-Determination Theory emphasizes intrinsic motivation, suggesting that people are inherently motivated by needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness. This theory posits that when these psychological needs are met, individuals experience greater well-being and engagement. Together, these alternative theories offer more comprehensive and versatile answers to the enduring question of what truly explains human motivation.

Takeaway: Drive Reduction Theory, while historically significant, provides a foundational but incomplete picture of what truly explains human motivation. It effectively illustrates how basic physiological needs like hunger and thirst compel us to act to restore balance. However, the vast array of human behaviors – from pursuing complex goals to seeking thrilling adventures – demonstrates that our motivations extend far beyond simple drive reduction.

Action: Reflect on your own daily motivations. Can you identify behaviors driven purely by physiological needs? How do these compare to actions motivated by external rewards, personal growth, or the pursuit of an optimal arousal level? Understanding these different motivational forces can offer profound insights into your own choices and aspirations.