Have you ever felt so disconnected from reality that it felt like you were watching your own life unfold from a distance? This profound sense of detachment, known as dissociation, is a complex psychological phenomenon that often impacts individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD). For those living with BPD, dissociation borderline personality can manifest as a powerful coping mechanism, yet it frequently disrupts daily functioning and relationships. Understanding these dissociative experiences is crucial for effective management and improved mental well-being.

What is dissociation in borderline personality disorder? Dissociation in borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a psychological state where thoughts, emotions, behaviors, perceptions, memories, and identity feel profoundly disconnected. This can range from mild daydreaming to severe episodes of feeling detached from one’s body or surroundings, often triggered by stress or trauma. Approximately 75-80% of individuals with BPD report experiencing stress-related dissociation (Harvard, 2024).

1. Understanding Dissociation in BPD

Dissociation, at its core, represents a psychological defense mechanism where there is an involuntary break in how your mind processes information. While everyone might experience mild forms of dissociation from time to time—like getting lost in a book or zoning out during a long drive—for individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD), these experiences can be far more intense, frequent, and disruptive. The profound sense of unreality or detachment associated with dissociation in BPD is often a direct response to overwhelming stress, emotional dysregulation, or re-experiencing past trauma. It serves as a mental escape, allowing the individual to temporarily disconnect from distressing feelings or situations that feel too painful to confront directly.

This phenomenon is not merely a fleeting distraction; severe dissociative episodes can significantly impair a person’s ability to function in their day-to-day life. It can impact their relationships, work or academic performance, and overall sense of self. The experience of dissociation borderline personality can make it challenging to maintain a coherent sense of identity or reality, leading to feelings of confusion, fear, and isolation. Recognizing these patterns is the first step toward effective management and fostering a more integrated sense of self. Understanding the nuances of these experiences is vital for both individuals with BPD and their support networks, paving the way for targeted interventions and empathetic understanding.

2. Exploring the Spectrum of Dissociative Symptoms

The manifestations of dissociation in BPD are varied, extending far beyond simple daydreaming into more severe and distressing experiences. While mild forms might include zoning out during a conversation or momentarily forgetting what you were doing, individuals with BPD often report more profound and frequent episodes, especially during periods of intense emotional stress. These symptoms can be deeply unsettling and contribute to the overall distress experienced by someone navigating BPD. Researchers have identified several distinct types of dissociative experiences that are commonly reported within the context of borderline personality dissociation.

One common symptom is depersonalization, a pervasive feeling of being an outside observer of one’s own body or mental processes. Individuals describe it as feeling unreal, like they are in a dream, or as if they are watching themselves from a distance, unable to fully connect with their physical self. For example, a person might look at their hands and feel no connection to them, as if they belong to someone else. Another significant symptom is derealization, which involves feeling detached from the external world. Familiar surroundings may suddenly appear strange, unreal, or unfamiliar, as if one is living in a movie or a distorted reality. An individual might be in their own home, yet perceive their living room as an unfamiliar, unsettling space. Often, depersonalization and derealization occur simultaneously, amplifying the sense of unreality.

Furthermore, some individuals experience dissociative amnesia, which involves “losing time” – periods ranging from minutes to hours or even days where they cannot recall what they were doing or where they were, despite having been awake and functional. This can be deeply frightening, leading to gaps in memory and a fragmented sense of personal history. Imagine driving to a familiar destination and suddenly realizing you have no memory of the past 15 minutes of your journey. Identity confusion is another key symptom, characterized by a profound inner struggle about one’s true identity, often making it difficult to understand one’s place in relationships or distinguish where one’s own identity ends and another’s begins. Finally, identity alteration involves a sense of acting like a different person, with changes in mood or behavior that feel outside of one’s control. For instance, an individual might suddenly find themselves speaking in a different tone or performing a skill they don’t recall learning, often noted by others who observe a significant shift in their demeanor. These intense and varied forms of dissociation borderline personality underscore the complex internal world of those affected.

3. The Roots of Dissociation: Trauma and Brain Function

The precise mechanisms underlying dissociation, particularly in the context of borderline personality disorder, are still being thoroughly investigated in 2025. However, a significant body of research points to a strong correlation between dissociative experiences and a history of repetitive, overwhelming trauma. This is especially true for severe childhood abuse or neglect, which can profoundly shape an individual’s psychological development and their coping strategies. Dissociation often emerges as the brain’s ingenious, albeit maladaptive, way of coping with unbearable pain and stress. By creating a mental separation from the traumatic event, the individual can emotionally detach, making the experience somewhat more tolerable in the moment.

This learned coping mechanism, developed during formative years, can become deeply ingrained. If a child repeatedly used dissociation to manage extreme stress or fear, this pattern can persist into adulthood, influencing how they react to current stressful situations. The brain essentially “learns” to dissociate as a default response to perceived threats or overwhelming emotions, even when the immediate danger is no longer present. It’s crucial to understand that while trauma is a significant risk factor, it is not a universal prerequisite for dissociation in BPD. Not everyone who experiences trauma will develop dissociative symptoms, and conversely, some individuals may experience dissociation without a clear history of severe trauma.

Beyond psychological coping mechanisms, emerging research is also exploring the neurobiological underpinnings of dissociation. There is increasing evidence suggesting that actual changes in brain function and communication might contribute to the experience of borderline personality dissociation. These neurobiological factors, combined with psychological vulnerabilities and environmental stressors, create a complex interplay that contributes to the development and persistence of dissociative symptoms. Understanding this multifaceted etiology is key to developing more effective and targeted interventions for those struggling with these challenging experiences.

4. Latest Research Insights into BPD Dissociation

Recent advancements in neuroimaging technology, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans, are providing unprecedented insights into the brain’s activity during dissociative episodes in individuals with borderline personality disorder. As of 2025, early research using these sophisticated techniques has begun to identify specific changes in brain function and communication that may underpin dissociation in BPD. These findings are crucial for moving beyond purely psychological explanations and understanding the biological components that contribute to these complex symptoms.

Studies have indicated that individuals experiencing dissociative symptoms, particularly those with BPD, often show decreased activity in the limbic temporal areas of the brain. These regions are critical for processing emotions, memory, and social cognition. Simultaneously, researchers have observed increased activity in the frontal areas of the brain, which are associated with executive functions like reasoning, planning, and self-control. This imbalance—a reduction in emotional processing areas and an increase in cognitive control areas—suggests that the brain might be actively attempting to suppress or disconnect from overwhelming emotional input, leading to the subjective experience of detachment. Furthermore, changes in communication pathways between these distinct brain regions have been observed, indicating a disruption in the integrated processing of sensory and emotional information.

These key findings from neuroimaging research hold significant implications for the future of BPD treatment. By pinpointing the specific brain processes related to dissociation borderline personality, researchers can work towards developing more targeted and effective psychotherapeutic interventions. For instance, understanding which neural circuits are underactive or overactive during dissociation could lead to new biofeedback techniques or adjunct therapies designed to modulate these brain states. The goal is to make psychotherapy more precise and beneficial, helping individuals to re-integrate their experiences and reduce the frequency and intensity of dissociative episodes. This cutting-edge research promises to enhance our understanding and treatment of dissociative experiences in BPD in the coming years.

5. Proven Therapeutic Approaches and Grounding Techniques

Effectively managing dissociation in borderline personality disorder involves a multi-pronged approach, often rooted in evidence-based psychotherapies. Treatments specifically designed for BPD, such as Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), inherently include components aimed at reducing dissociative symptoms by enhancing emotional regulation, distress tolerance, and mindfulness skills. The primary goal of these therapeutic interventions is to help individuals reconnect with themselves, the present moment, and their immediate surroundings, thereby counteracting the detachment characteristic of dissociation in BPD. A core element of this re-connection process involves learning and consistently practicing grounding techniques.

Grounding is an invaluable skill that helps individuals experiencing dissociation to bring their focus back to the present reality, leveraging their five senses to anchor themselves. These exercises are particularly effective because they engage external stimuli, distracting the mind from internal distress and fostering a sense of embodiment. For instance, a visual grounding exercise might involve meticulously observing small details in the environment: identifying five blue objects, naming four sounds you can hear, noticing three textures, identifying two distinct smells, and tasting one flavor (like a mint). This systematic engagement of the senses helps to pull the mind away from dissociative states and re-establish contact with the here and now.

Beyond visual exercises, other sensory grounding techniques can be highly effective. Holding an ice cube for a few moments allows the intense cold sensation to serve as a powerful anchor, drawing attention to physical reality. Chewing a strong piece of minty gum or smelling a lemon can similarly provide an immediate, distinct sensory input that helps to break the dissociative spell. These simple, yet powerful, techniques empower individuals to actively manage their borderline personality dissociation in moments of distress. Regular practice of these self-help strategies, often learned and refined in therapy, builds resilience and provides concrete tools for navigating the challenging landscape of dissociative experiences, significantly improving overall quality of life (Harvard, 2024).

6. Beyond BPD: Other Dissociative Conditions

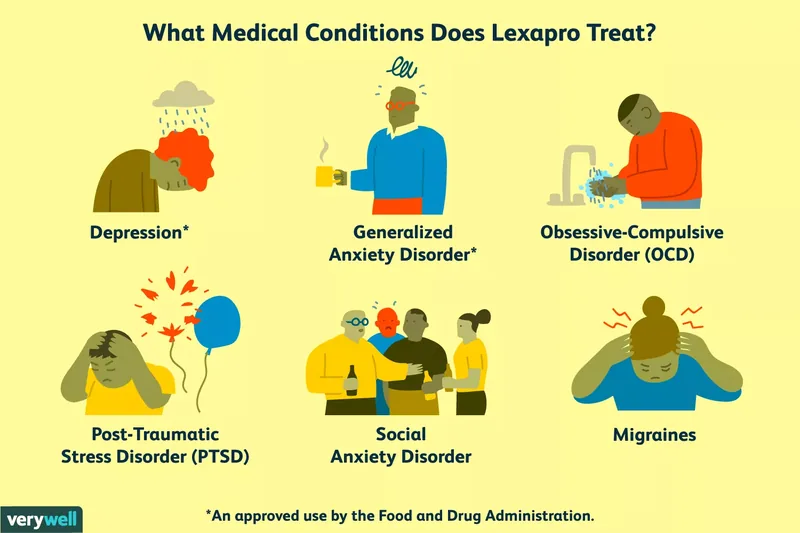

While dissociation in BPD is a significant and often debilitating symptom, it is important to recognize that dissociation can also be a central feature of other distinct mental health conditions. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), there are several primary dissociative disorders where dissociation is not merely a symptom, but the defining characteristic of the condition. Understanding these distinctions is vital for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment planning, ensuring that individuals receive the most effective support for their unique challenges.

Two of the main dissociative disorders include Dissociative Amnesia and Depersonalization/Derealization Disorder. Dissociative Amnesia is characterized by an inability to recall important personal information, usually of a traumatic or stressful nature, that is too extensive to be explained by ordinary forgetfulness. This can manifest as localized amnesia (forgetting a specific event), selective amnesia (forgetting parts of an event), or generalized amnesia (complete loss of memory for one’s life history). Depersonalization/Derealization Disorder, as previously discussed, involves persistent or recurrent experiences of feeling detached from one’s own body or mental processes (depersonalization) and/or feeling detached from one’s surroundings (derealization), causing significant distress or impairment.

Perhaps the most widely recognized and severe dissociative disorder is Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), formerly known as Multiple Personality Disorder. DID is characterized by the presence of two or more distinct personality states, or “alters,” each with its own relatively enduring pattern of perceiving, relating to, and thinking about the environment and self. These distinct identities recurrently take control of the person’s behavior, often accompanied by gaps in the recall of everyday events, important personal information, and traumatic events. A profound history of severe childhood abuse, including physical and/or sexual abuse and neglect, is overwhelmingly common among individuals diagnosed with DID. Treating severe dissociative symptoms, whether in BPD or other dissociative disorders, through therapy can be an intense and emotionally demanding process. It often necessitates confronting and processing past traumas. While challenging, therapeutic interventions provide the necessary tools and support to learn to cope with these symptoms, integrate fragmented experiences, and significantly improve one’s quality of life, fostering a more coherent and stable sense of self.