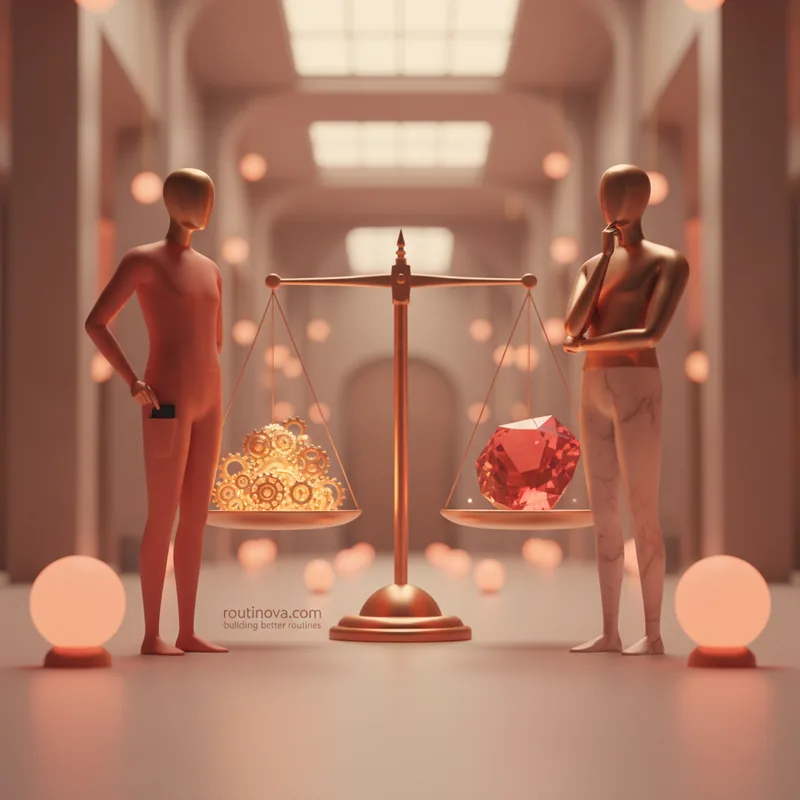

Have you ever paused to wonder why, in situations demanding collective effort, individuals sometimes opt for self-interest over mutual benefit? This fundamental human tendency, where betrayal can seem more appealing than cooperation, is a cornerstone of human behavior. Understanding the psychology behind why people make these choices often leads us to a powerful concept from game theory: the Prisoner's Dilemma. This scenario elegantly illustrates the conflict between personal gain and collective well-being, revealing how rational decisions can paradoxically lead to suboptimal outcomes for everyone involved.

Unraveling the Prisoner's Dilemma: A Core Concept

The Prisoner's Dilemma is a foundational concept in psychology and economics, designed to explain the intricate balance between self-interest and collective welfare. Developed in 1950 by mathematicians Merrill Flood and Melvin Dresher for the Rand Corporation, it was initially conceived to model complex Cold War strategies, such as the arms race between nations (Kuhn, 1997).

Later, Albert W. Tucker popularized the scenario involving two prisoners, making the concept more accessible. Imagine two suspects, arrested for a crime, interrogated separately without any means of communication. Each is presented with a choice: betray their accomplice by confessing, or remain silent. The outcome for each prisoner hinges entirely on the other's decision, creating a fascinating interplay of trust and suspicion.

The Possible Outcomes of Betrayal and Cooperation

- One betrays, one cooperates: If one prisoner confesses (defects) and the other stays quiet (cooperates), the defector goes free, while the cooperator receives a heavy 10-year sentence.

- Both cooperate: If both prisoners remain silent, demonstrating cooperation, they each receive a lighter sentence of 1 year.

- Both betray: If both confess, betraying each other, they each receive a moderate sentence of 5 years.

Intuitively, the best collective outcome for both prisoners is to cooperate and stay silent, leading to the shortest combined sentence. However, the rational choice for an individual, aiming to minimize their own punishment, is often to betray. The fear of being exploited by the other -- of staying silent only for the partner to confess and walk free -- drives individuals towards defection, even if it leads to a worse outcome for both (Tobin, 2023).

The Dilemma in Daily Life: When Self-Interest Prevails

The Prisoner's Dilemma isn't confined to hypothetical prison cells; its principles resonate across countless real-world scenarios, shedding light on the psychology behind why individuals and groups struggle with cooperation. From personal relationships to global politics, the tension between individual gain and collective good is ever-present.

Everyday Examples of the Dilemma in Action

- Group Projects: In a team assignment, each member faces a choice: contribute fully (cooperate) or do minimal work, hoping others will pick up the slack (betray). If everyone cooperates, the project is excellent, and everyone benefits. If one slacks and others work hard, the slacker benefits most. But if everyone slacks, the project fails, and all suffer. The fear of being the only one working hard often leads to reduced individual effort.

- Public Transport Etiquette: Consider holding a door for others on a crowded train. Cooperating means waiting, potentially delaying yourself slightly, but benefiting everyone. Defecting means rushing through, saving a few seconds. If everyone cooperates, the flow is smooth. If everyone defects, it's chaotic. The immediate, tangible benefit of saving a second often outweighs the less tangible collective benefit.

- Online Reviews: When asked to review a product or service, consumers can provide honest, constructive feedback (cooperate) or leave an overly positive/negative review for personal gain, like a discount or to harm a competitor (betray). Honest reviews benefit the broader consumer community. However, the temptation for a personal perk or competitive advantage can lead to biased reviews, ultimately eroding trust for everyone (Harvard, 2024).

These examples highlight a crucial insight: the self-interested gain is often immediate and tangible, while the collective gain is long-term and less direct. This disparity makes it challenging for individuals to prioritize cooperation, even when it's logically the superior choice for all involved. Environmental issues, like overfishing or deforestation, perfectly mirror this dilemma, where short-term individual exploitation leads to devastating long-term collective harm.

Navigating Complex Scenarios: Iterated Dilemmas and Strategic Choices

While the classic Prisoner's Dilemma is a single-round game, many real-world interactions are repeated. This introduces the concept of the iterated Prisoner's Dilemma, where players engage in multiple rounds, allowing for the development of trust, reputation, and strategic responses. These multi-round, multi-player versions can model highly complex social interactions, from family dynamics to international relations.

The Power of Tit-for-Tat in Fostering Cooperation

In iterated dilemmas, various strategies emerge, but one of the most successful is known as Tit-for-Tat. This strategy is remarkably simple yet highly effective, built on two core principles:

- Start with cooperation: In the very first interaction, always choose to cooperate.

- Reciprocate: In every subsequent interaction, do whatever your opponent did in the previous round.

Tit-for-Tat's success lies in its balance of kindness and firmness. It's 'nice' because it begins with cooperation, signaling a willingness to collaborate. It's 'provocable' because it immediately retaliates against betrayal, preventing exploitation. Crucially, it's also 'forgiving,' returning to cooperation as soon as the opponent does. This strategy reveals the psychology behind why a consistent, reciprocal approach can effectively encourage cooperation and deter persistent defection in ongoing relationships.

"Tit-for-Tat teaches that defection will be acknowledged and punished with defection, and that a return to cooperation will be rewarded," explains game theory experts (Mayo Clinic, 2023).

In practical terms, groups can leverage Tit-for-Tat principles to foster collective good. By establishing clear expectations for initial cooperation and consistently responding to both cooperative and uncooperative actions, organizations and communities can build environments where mutual benefit is prioritized over individual selfishness.

Limitations and Nuances: Beyond Binary Choices

Despite its profound insights, the Prisoner's Dilemma is not without its criticisms and limitations. Its strength lies in its elegant simplification of complex human interactions into binary choices (cooperate or defect). However, real-world decisions are rarely so straightforward, often involving multiple options, varying degrees of trust, and nuanced motivations.

Critics argue that the dilemma doesn't fully account for the richness of human psychology, particularly the long-term impact of relationships, reputation, and emotional factors. In reality, individuals don't operate in a vacuum; their decisions are influenced by past experiences with others, their perceived social standing, and the potential for future interactions. These elements can significantly alter the perceived 'rational' choice, making cooperation more appealing than a purely self-interested analysis might suggest.

Nevertheless, even with these simplifications, the Prisoner's Dilemma remains an invaluable tool. It offers a powerful framework for understanding the psychology behind why conflict arises between individual and collective interests. By studying its dynamics, we gain deeper insights into the conditions that either foster or hinder cooperation, providing a lens through which to analyze everything from economic competition to climate change negotiations. It reminds us that while self-interest is a potent force, the potential for mutual benefit often lies just beyond the fear of betrayal.