The Electra complex is a significant, albeit controversial, concept within psychoanalytic theory. Often described as the female counterpart to the more widely known Oedipus complex, it delves into the intricate psychosexual development of young girls. In essence, the Electra complex psychoanalytic framework suggests that a girl develops unconscious competitive feelings toward her mother for her father’s affection and attention. This complex phase, theorized to occur during early childhood, plays a crucial role in forming a girl’s identity, gender roles, and future relationships, according to classical Freudian thought.

This guide provides a comprehensive exploration of the Electra complex, tracing its historical roots, understanding its proposed mechanisms, and examining its relevance in contemporary psychology. We’ll uncover how this theory attempts to explain certain aspects of female development and why it continues to spark debate among mental health professionals.

1. What is the Electra Complex?

The Electra complex, in psychoanalytic theory, describes a phase in a young girl’s development where she experiences an unconscious sexual attraction to her father and a corresponding rivalry with her mother. This emotional dynamic is posited as a critical stage for a girl to navigate in order to establish her sense of self and gender identity. It’s essentially the female version of the Oedipus complex, which describes similar dynamics in boys.

This concept suggests that girls may display behaviors such as seeking exclusive attention from their fathers, exhibiting jealousy towards their mothers, or even trying to emulate their mothers to win paternal approval. While the term is broadly recognized, its acceptance as a valid psychological phenomenon has significantly diminished over time. Most contemporary psychologists view the Electra complex psychoanalytic concept as an outdated historical artifact rather than a scientifically supported theory. However, it remains a foundational element in understanding the historical trajectory of psychoanalytic thought.

2. Origins and History of the Term

While often attributed to Sigmund Freud, the term “Electra complex” was actually coined by Carl Jung in 1913. Jung, a former protégé of Freud, introduced the term to draw a clear parallel between the psychosexual developmental struggles of girls and boys. The name itself is derived from the ancient Greek myth of Electra, who, alongside her brother Orestes, sought revenge for their father Agamemnon’s murder by their mother Clytemnestra and her lover. This mythological narrative of a daughter’s intense loyalty to her father and hostility toward her mother provided a potent metaphor for Jung’s concept.

Freud, despite developing the underlying theoretical framework, never fully embraced Jung’s terminology. He preferred to describe the phenomenon as the “feminine Oedipus attitude” or the “negative Oedipus complex,” emphasizing its analogous nature to the male Oedipus complex rather than a distinct entity. The divergence in terminology and theoretical emphasis contributed to the eventual intellectual schism between Freud and Jung, highlighting their differing views on the role of sexuality in human motivation and development. This historical context is crucial for understanding the nuances of the Electra complex psychoanalytic model and its place within early psychoanalysis (Harvard, 2024).

3. Freud’s View: The Feminine Oedipus Attitude

Sigmund Freud’s original conceptualization of female psychosexual development laid the groundwork for what Jung would later term the Electra complex. Freud believed that during the phallic stage (roughly ages three to six), girls initially identify with their mothers. However, upon discovering the anatomical difference between sexes—the absence of a penis—girls develop what he called “penis envy.” This envy leads to a resentment of the mother, whom they blame for their perceived “castration” or lack thereof.

This shift in affection results in the girl turning her desires towards her father, viewing him as the one who possesses the coveted organ and can potentially “give” her a baby as a substitute. This intense, unconscious longing for the father and competition with the mother constitutes Freud’s “feminine Oedipus attitude.” According to Freud, the successful resolution of this complex involved the girl eventually repressing her desire for her father and identifying with her mother, internalizing her mother’s values and adopting female gender roles. This complex interplay of envy, desire, and identification was central to Freud’s understanding of how female identity and sexuality formed within the Electra complex psychoanalytic framework (Harvard, 2024).

4. How the Electra Complex Manifests in Childhood

The Electra complex, according to its proponents, is a largely unconscious process that manifests through various behaviors in young girls during the phallic stage of psychosexual development. This period, typically between the ages of three and six, is characterized by children’s growing awareness of their bodies and gender differences. In a girl experiencing the Electra complex, manifestations might include a noticeable increase in affectionate gestures towards her father, often accompanied by a subtle or overt rejection of her mother’s attention.

For instance, a young girl might insist on sitting exclusively next to her father at the dinner table, demand he read her bedtime stories, or express a desire to “marry” her daddy when she grows up. Concurrently, she might exhibit jealousy when her parents show affection to each other, or engage in minor acts of defiance or competition with her mother for her father’s time. These behaviors, Freud suggested, are not conscious manipulations but rather outward expressions of deeper, unconscious libidinal urges and rivalries. A girl might even try to mimic her mother’s appearance or behaviors to better attract her father’s attention, demonstrating the complex internal struggle within the Electra complex psychoanalytic dynamic. An example could be a child demanding a new dress “just like Mommy’s” when preparing for an outing with Dad.

5. The Process of Resolution

According to classical psychoanalytic theory, the successful resolution of the Electra complex is a crucial step in a girl’s healthy psychosexual development and the formation of her superego. The process involves several psychological defense mechanisms. Initially, the girl’s unconscious desires for her father and rivalry with her mother become too overwhelming or anxiety-provoking. To alleviate this internal conflict, these urges are repressed, pushed out of conscious awareness.

The pivotal moment for resolution, as Freud described, involves the girl accepting her lack of a penis and redirecting her desires. She relinquishes her primary attachment to her father and, out of fear of losing her mother’s love and recognizing her mother as a powerful figure, begins to identify with her. This identification is not merely an imitation but a profound internalization of her mother’s personality traits, values, and gender roles. Through this process, the girl adopts feminine characteristics, learns appropriate societal behaviors, and develops a sense of morality (her superego). This resolution is believed to pave the way for healthy adult relationships, as the girl moves past the intense, early childhood attachments. The Electra complex psychoanalytic perspective views this as essential for establishing a stable sense of self and preparing for future heterosexual relationships (Harvard, 2024).

6. Modern Psychological Perspectives (2025 Context)

In 2025, the Electra complex is largely viewed by mainstream psychology as an outdated and scientifically unsupported theory. While it holds significant historical importance in the development of psychoanalysis, its core tenets, particularly those related to “penis envy” and rigid gender roles, are widely rejected. Modern psychological research emphasizes the complex interplay of biological, social, and cultural factors in gender identity and sexual development, moving far beyond Freud’s singular focus on anatomical differences and specific psychosexual stages.

Contemporary perspectives highlight that children learn about gender roles and relationships through observation, social learning, and interaction with a diverse range of caregivers, not solely through an unconscious competition for a parent’s affection. For example, a child’s understanding of self is shaped by media, peer groups, and educational environments, rather than just the dynamics within the nuclear family (Harvard, 2024). Furthermore, the original Electra complex psychoanalytic theory is criticized for its heteronormative assumptions, failing to account for the healthy development of children raised in LGBTQ+ families or single-parent households. Research consistently shows that children in diverse family structures thrive without experiencing these specific Freudian complexes. While the Electra complex offers an intriguing historical lens into early 20th-century thought, its practical application in contemporary mental health practice is minimal.

7. Implications for Understanding Relationships

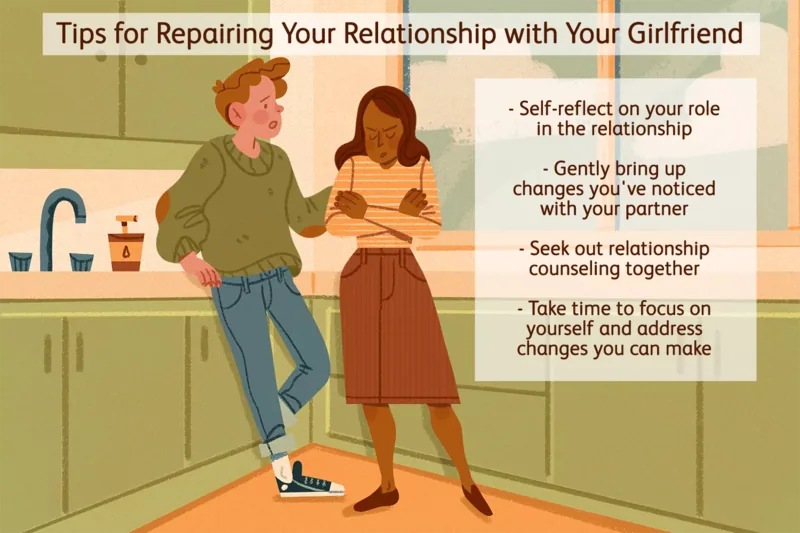

Despite its diminished scientific standing, the historical concept of the Electra complex can still spark discussions about the origins of certain relationship dynamics, particularly in popular culture. The idea of “daddy issues,” for instance, which is often loosely linked to the Electra complex, suggests that a woman’s early relationship with her father might influence her adult romantic choices or attachment styles. While contemporary psychology uses more empirically supported frameworks like attachment theory to explain such influences, the Electra complex psychoanalytic concept provided an early, albeit flawed, attempt to connect childhood experiences with adult relational patterns.

Understanding the historical context of such theories helps us appreciate the evolution of psychological thought. It underscores how early attempts to categorize complex human emotions, even if inaccurate by today’s standards, paved the way for more nuanced and evidence-based research. For example, modern attachment theory posits that early interactions with primary caregivers (of any gender) can shape an individual’s expectations and behaviors in adult relationships, focusing on security, trust, and communication rather than unconscious sexual rivalry. While the Electra complex itself is no longer a diagnostic or explanatory tool, its legacy encourages continued exploration into how our earliest family dynamics contribute to who we become in our relationships.