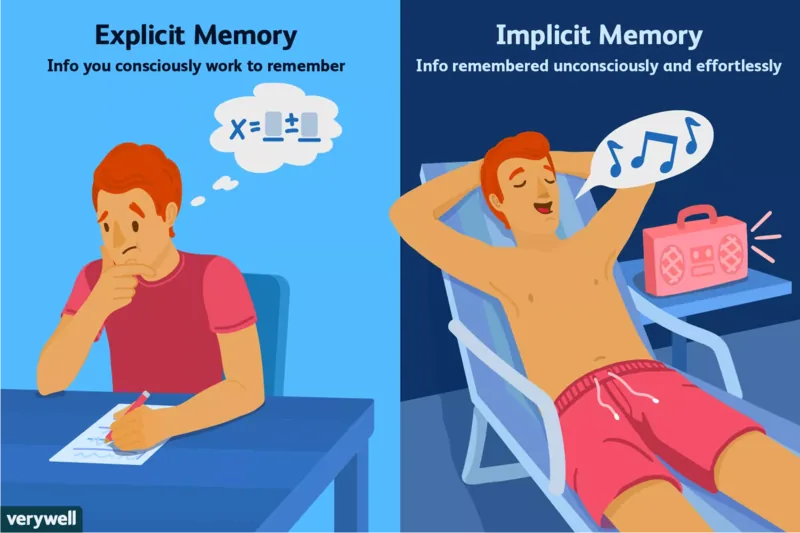

Memory is a cornerstone of human experience, enabling us to learn, grow, and navigate the world. But not all memories are created equal. While some recollections spring to mind effortlessly, others demand conscious effort. Understanding the difference between implicit and explicit memory is key to appreciating the intricate workings of our minds. These two fundamental types of long-term memory play distinct yet interconnected roles in our daily lives, from performing routine tasks to recalling significant life events.

Explicit memory involves the conscious recall of facts and events, like remembering a friend’s birthday or a historical date. In contrast, implicit memory allows us to perform actions without conscious thought, such as riding a bike or typing on a keyboard. Both are crucial for our ability to function and adapt, influencing our knowledge and behavior in profound ways. This guide will delve into these fascinating memory systems, exploring their mechanisms, distinctions, and how they collectively shape our understanding and interaction with the environment.

Understanding Implicit Memory: The Unseen Architect of Skills

Implicit memory, often referred to as unconscious or automatic memory, governs the knowledge we acquire and utilize without conscious awareness or intentional recall. This type of memory is nondeclarative, meaning you cannot verbally articulate or consciously bring these memories into your awareness. Instead, implicit memories manifest through performance, influencing our actions and perceptions automatically.

A significant component of implicit memory is procedural memory, which encompasses our ability to perform learned skills and habits. Think about how you tie your shoelaces, play a musical instrument, or navigate a familiar route while driving. These complex sequences of actions become second nature, requiring no deliberate thought once mastered. The cerebellum and basal ganglia are key brain regions involved in the formation and storage of these procedural memories, acting as the brain’s “skill centers” (Michigan State University, 2024). The difference between implicit and explicit memory is stark here, as explicit memories demand conscious retrieval.

Beyond procedural skills, implicit memory also includes phenomena like priming. Priming occurs when exposure to a stimulus influences a subsequent response, even if the initial exposure was unconscious. For instance, if you recently saw the word “doctor,” you might be quicker to recognize the word “nurse” later, even if you don’t consciously remember seeing “doctor.” This subtle influence highlights how past experiences shape our present processing without our knowledge. Another facet is classical conditioning, where an involuntary response becomes associated with a new stimulus, such as flinching at the sound of a dentist’s drill.

Examples of implicit memory are abundant in daily life. Imagine humming along to a song you’ve heard many times without actively trying to memorize the lyrics; your implicit memory allows you to recall the melody and words effortlessly. Typing on a keyboard, where your fingers instinctively find the right keys, is another prime example. Even after years of not riding a bicycle, most individuals can hop on and ride with surprising ease, demonstrating the enduring nature of these unconscious motor memories. New examples include the muscle memory involved in playing a complex piano piece, instinctively swerving to avoid an obstacle while driving, or automatically understanding the grammar of your native language without conscious rule application. These are skills embedded deeply, guiding our actions without requiring a conscious mental checklist.

Exploring Explicit Memory: Your Conscious Vault of Knowledge

Explicit memory, also known as declarative memory, refers to memories that can be consciously recalled and verbalized. This is the memory system we typically think of when we talk about “remembering” something, as it involves intentional retrieval of information. Explicit memories are foundational for learning facts, recalling personal experiences, and building our understanding of the world. The hippocampus and frontal lobe are critical brain structures for encoding and retrieving these conscious memories (Michigan State University, 2024).

This form of memory is broadly categorized into two main types: episodic memory and semantic memory. Episodic memory is our autobiographical record, storing specific events and experiences from our lives, complete with contextual details like time, place, and associated emotions. Recalling your high school graduation, what you had for breakfast yesterday, or a memorable vacation are all examples of episodic memory. These memories are often vivid and deeply personal, forming the narrative of our individual histories. They allow us to mentally “re-experience” past moments, giving depth to our personal identity.

Semantic memory, on the other hand, deals with general knowledge, facts, concepts, and ideas that are not tied to specific personal experiences. This includes things like knowing the capital of France, understanding the meaning of words, recalling mathematical formulas, or identifying historical figures. Semantic memory forms the basis of our general understanding of the world, allowing us to learn, reason, and communicate effectively. It’s the information we typically learn in school or through general knowledge acquisition. While episodic memory is about “remembering that,” semantic memory is about “knowing that.”

Examples of explicit memory are numerous and integrated into our daily routines. Remembering items on a grocery list, recalling your best friend’s birthday, or studying for an exam all rely heavily on explicit memory. New examples include remembering a specific conversation you had last week, recalling the plot of a book you recently read, or consciously trying to learn and remember vocabulary for a new language. These tasks require deliberate effort to encode the information and then consciously retrieve it when needed. The ability to articulate these memories, to declare them, is what sets explicit memory apart.

The Profound Difference Between Implicit and Explicit Memory

The difference between implicit and explicit memory lies primarily in their accessibility to conscious awareness and the way they are formed and retrieved. Explicit memories are conscious and declarative, meaning they can be intentionally brought to mind and verbally expressed. They are often formed through deliberate learning, rehearsal, and focused attention. In contrast, implicit memories are unconscious and nondeclarative, influencing behavior without requiring conscious thought or verbal articulation. They are typically acquired through repetition and practice, becoming automatic over time.

Consider the classic example of typing on a keyboard. When you type a sentence, your fingers move automatically, finding the correct keys without you consciously thinking about each letter’s location. This is implicit memory in action – a procedural skill developed through consistent practice. If someone then asks you to name all the letters in the top row of the keyboard without looking, you would likely struggle. This task requires explicit memory, which you probably haven’t intentionally encoded or rehearsed (Harvard, 2024). The keyboard layout is not a consciously memorized fact for most, illustrating the clear distinction between knowing how to do something and knowing what something is.

Another key distinction is how these memories are triggered and used. Explicit memories are often context-dependent, relying on specific cues or associations for retrieval. For instance, remembering a particular event might be easier when you are back in the place where it happened. Implicit memories, however, often manifest through automatic responses or improved performance, such as responding faster to a word you were primed with earlier. They are less about conscious retrieval and more about unconscious influence on behavior.

The learning process also highlights the difference between implicit and explicit memory. Explicit memories are often formed through effortful processing, requiring active engagement and attention. You consciously decide to learn a new fact or remember an event. Implicit memories, on the other hand, are often formed through incidental learning or repeated exposure. You don’t “try” to learn how to ride a bike; you just do it repeatedly until the skill becomes ingrained. This makes implicit memories remarkably robust and resistant to forgetting, even in cases of amnesia where explicit memory is severely impaired. The table below summarizes these core distinctions, emphasizing their unique characteristics and functions.

| Feature | Explicit Memory | Implicit Memory |

|---|---|---|

| Consciousness | Conscious, declarative, intentional recall | Unconscious, nondeclarative, automatic influence |

| Formation | Deliberate learning, rehearsal, attention | Repetition, practice, incidental learning |

| Retrieval | Intentional, effortful, context-dependent | Automatic, effortless, performance-based |

| Examples | Facts, events, names, dates, recipes | Skills (riding a bike, typing), habits, priming |

| Brain Areas | Hippocampus, frontal lobe | Cerebellum, basal ganglia |

Influences on Memory: How Stress, Mood, and Age Shape Recall

The efficiency and integrity of both implicit and explicit memory are not static; they are profoundly influenced by a variety of internal and external factors. Understanding these influences is crucial for maintaining optimal cognitive function and appreciating the dynamic nature of our memory systems. Environmental stressors, emotional states, and the natural process of aging can all leave their mark on how we encode, store, and retrieve information.

Stress, particularly chronic or severe stress, has a complex and often detrimental impact on memory. High levels of stress hormones, like cortisol, can impair the function of the hippocampus, a brain region vital for explicit memory formation (Harvard, 2024). This can lead to difficulties in learning new information or recalling specific facts and events. For instance, trying to remember details during a highly stressful presentation might prove challenging. While some research suggests that stress might actually facilitate the formation of implicit memories for negative emotional information, its overall effect on explicit memory is often negative. However, recent studies indicate that normal, everyday fluctuations in stress may not significantly impair working memory, highlighting the importance of distinguishing between acute and chronic stress levels (Lukasik et al., 2019).

Mood also plays a significant role in memory, particularly through a phenomenon known as mood-congruent memory. Individuals experiencing depressed moods, for example, are more likely to exhibit implicit recall of negative information, while those in positive moods might implicitly recall positive information more readily (Gaddy & Ingram, 2014). This suggests that our emotional state can bias the types of memories that are unconsciously activated or more easily accessible. For explicit memory, a positive mood can sometimes enhance memory encoding and retrieval, while extreme negative emotions can interfere with focused attention, thus hindering explicit recall. This interplay underscores the deep connection between our emotional well-being and cognitive function.

Age is another prominent factor influencing memory. While explicit memory, particularly episodic memory, tends to show a gradual decline with age, implicit memories generally remain remarkably preserved (Ward et al., 2013). Older adults might find it harder to recall specific details of recent events or learn new factual information as quickly as younger individuals. However, their ability to perform well-learned skills, like riding a bike or playing a musical instrument, often remains intact. This resilience of implicit memory highlights its fundamental and robust nature, suggesting different neurological mechanisms and vulnerabilities compared to explicit memory. Understanding these age-related changes can help in developing targeted interventions to support memory function across the lifespan.

The Synergy: How Implicit and Explicit Memory Collaborate Daily

While the difference between implicit and explicit memory is clear, these two systems rarely operate in isolation. In fact, for most complex daily tasks, implicit and explicit memory work in seamless synergy, allowing us to interact with our environment efficiently and effectively. This collaboration ensures that we can both consciously plan and unconsciously execute, creating a fluid and adaptive cognitive experience. The interplay between these memory types is essential for everything from navigating a city to preparing a meal.

Consider the act of driving a car. Your implicit memory is heavily engaged in the procedural aspects: steering, braking, accelerating, and shifting gears. These are skills you execute automatically, without consciously thinking about each individual movement. Simultaneously, your explicit memory is at work as you consciously recall the specific route to your destination, remember traffic laws, or interpret road signs. If you encounter a new detour, your explicit memory helps you process the new information and adapt, while your implicit memory continues to handle the mechanics of driving. This dual activation allows for efficient navigation without being overwhelmed by conscious processing of every single action.

Another excellent example is cooking a meal from a recipe. Your implicit memory allows you to perform basic kitchen tasks effortlessly, such as chopping vegetables, boiling water, or stirring ingredients. These are ingrained skills that don’t require conscious thought. However, your explicit memory is crucial for recalling the specific ingredients listed in the recipe, remembering the cooking times, and following the sequence of steps. Without the conscious recall of the recipe (explicit memory), the implicit skills would be aimless; without the automatic execution of culinary techniques (implicit memory), following the recipe would be a slow and arduous process. Together, they enable you to create a delicious dish with relative ease.

Learning a new sport or musical instrument also showcases this powerful collaboration. Initially, you rely heavily on explicit memory to learn the rules, techniques, and notes. You consciously think about how to hold the racket, position your fingers on the guitar, or understand the strategy. With practice and repetition, these deliberate actions transition into implicit memory. The movements become automatic, the strategies intuitive, and the notes flow without conscious effort. At this stage, your explicit memory can then be freed up to focus on more complex aspects, such as improvising music or anticipating an opponent’s move, while your implicit memory handles the foundational motor skills. This dynamic interaction is fundamental to skill acquisition and mastery.

Actionable Strategies for Protecting and Enhancing Your Memory

Maintaining sharp memory function, encompassing both implicit and explicit types, is a lifelong endeavor that significantly contributes to overall well-being and cognitive health. Fortunately, numerous evidence-based strategies and lifestyle adjustments can help protect and even enhance your memory as you age. Integrating these habits into your daily routine can foster a more resilient and efficient memory system, allowing you to learn new skills and recall vital information with greater ease.

Prioritize Adequate Sleep: Sleep is not merely a period of rest; it’s a critical time for memory consolidation. During deep sleep stages, the brain actively processes and reorganizes memories, transferring them from temporary to more permanent storage (Harvard, 2024). Consistently getting 7-9 hours of quality sleep each night is paramount for strengthening both explicit memories (like facts learned during the day) and implicit memories (like motor skills). Poor sleep can impair attention and learning, directly hindering memory formation. Establishing a consistent sleep schedule and creating a conducive sleep environment can significantly benefit your cognitive functions.

Engage in Regular Physical Activity: Exercise is a powerful tool for brain health. Physical activity increases blood flow to the brain, delivering essential oxygen and nutrients, and stimulates the release of neurotrophic factors that promote the growth of new brain cells and connections (Harvard, 2024). Regular aerobic exercise, such as brisk walking, jogging, or swimming, has been shown to improve memory, particularly in areas related to explicit memory. Aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week. This not only benefits your physical health but also creates an optimal environment for memory function.

Embrace Mental Stimulation and Learning: Just like muscles, your brain benefits from regular exercise. Engaging in mentally challenging activities helps build cognitive reserve and strengthens neural pathways, which can protect against age-related memory decline. Learning a new language, mastering a musical instrument, solving puzzles, reading complex books, or acquiring a new hobby are excellent ways to keep your mind sharp. These activities stimulate various brain regions, enhancing both explicit memory for new information and implicit memory for learned skills. The difference between implicit and explicit memory means diverse activities benefit different systems.

Adopt a Brain-Healthy Diet: Your diet plays a crucial role in brain health. Foods rich in antioxidants, omega-3 fatty acids, and vitamins can help protect brain cells and support optimal cognitive function. Incorporate plenty of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats (like those found in fatty fish, nuts, and olive oil) into your diet. The Mediterranean diet, for example, has been linked to better cognitive function and a reduced risk of memory impairment. Limiting processed foods, sugary drinks, and excessive saturated fats can also contribute to better brain health over the long term.

Foster Social Connections and Manage Stress: Social interaction and emotional well-being are also vital for memory. Engaging in meaningful social activities can reduce feelings of isolation and depression, both of which can negatively impact cognitive function. Additionally, chronic stress can impair memory, particularly explicit memory. Practicing stress-reduction techniques such as mindfulness meditation, yoga, or deep breathing can help regulate stress hormones and protect your memory. A balanced lifestyle that includes social engagement and effective stress management creates a supportive environment for robust memory function.