In the annals of medical history, few terms carry as much baggage and misunderstanding as “hysteria.” Once a pervasive diagnosis for a bewildering array of symptoms, predominantly in women, hysteria is not what many people imagine it to be—a mere display of over-the-top emotions. Instead, it represents a fascinating and often troubling journey through the evolution of psychological understanding. This antiquated label has given way to sophisticated diagnoses like dissociative and somatic symptom disorders, reflecting a deeper, more empathetic comprehension of human mental health.

The historical concept of hysteria, rooted in ancient beliefs, painted a picture of a condition unique to the female anatomy, driven by a “wandering uterus” (Harvard, 2024). Today, we recognize that the symptoms once attributed to hysteria are complex manifestations of underlying psychological distress, affecting individuals across all genders. Understanding this shift is crucial for anyone seeking to grasp the true nature of these conditions in the modern era.

1. From Ancient Misconceptions to Modern Insight

The term “hysteria” boasts a history stretching back millennia, with roots in ancient Egyptian and Greek medicine. As early as 1900 BCE, Egyptians attributed a range of female ailments to a “spontaneous uterus movement,” a belief that persisted for centuries (Harvard, 2024). This ancient understanding firmly linked the condition to the female reproductive system, giving rise to the Greek word hystera, meaning “uterus.”

For a long time, the prevailing medical view was that women were uniquely susceptible to this disorder. Treatments ranged from placing foul-smelling substances near the vulva to the Greek physician Celsus’s suggestion that virginity and abstinence might offer a cure. These approaches underscore a deep-seated misunderstanding of the human body and mind, heavily influenced by societal norms of the time.

It wasn’t until the early 1600s that anatomist Thomas Willis challenged the uterine origin, proposing that hysteria originated in the brain. This groundbreaking shift opened the door for the possibility that men could also experience “hysterical” symptoms, though the term remained predominantly associated with women, particularly during the Victorian era. The second edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1968 still included “hysterical neurosis,” a term finally removed in 1980. This historical trajectory clearly illustrates that hysteria is not what we once believed it to be, but rather a reflection of evolving medical knowledge and societal biases.

The legacy of hysteria profoundly influenced the birth of psychoanalysis. Pioneers like Jean-Martin Charcot and Sigmund Freud studied women presenting with hysterical symptoms, often using hypnosis as a treatment. Freud’s work with Josef Breuer on “Anna O.” led to the development of the “talking cure,” a precursor to modern psychotherapy, demonstrating the profound impact of verbalizing one’s psychological distress. This historical context reveals how a misunderstood condition ultimately propelled forward our understanding of the mind, underscoring that the truth about hysteria is far more complex than its historical label.

2. Unpacking the Symptoms Once Labeled Hysteria

The array of signs and symptoms once grouped under the umbrella of “hysteria” was remarkably broad and often bewildering. These manifestations were primarily observed in women and could range from dramatic physical ailments to profound emotional disturbances. Common historical descriptions included blindness, partial paralysis, and even epileptic-like seizures, all without an identifiable physical cause (Harvard, 2024).

Beyond these physical presentations, individuals diagnosed with hysteria often exhibited pronounced emotional outbursts and what was termed “histrionic behavior,” characterized by being overly dramatic or excitable. Hallucinations, increased suggestibility, and a loss of sensation were also frequently reported. These symptoms, while seemingly disparate, were united under a single, vague diagnosis that often failed to capture the true complexity of the individual’s suffering.

Other associated symptoms included feeling as though in a trance, developing amnesia for personal events, or experiencing rigid or spasming muscles. The sheer variety of these presentations highlights why hysteria is not what any single modern diagnosis encompasses. Instead, these historical descriptions now align with specific criteria for conditions such as dissociative disorders, where consciousness, memory, and identity are interrupted, or somatic symptom disorders, where psychological distress manifests as physical symptoms.

For example, a sudden onset of blindness without neurological explanation, once labeled hysterical, would today be investigated as a potential conversion disorder, a type of functional neurological symptom disorder. Similarly, episodes of amnesia or a feeling of being detached from oneself would point towards dissociative amnesia or depersonalization/derealization disorder. The shift from a single, catch-all term to precise, evidence-based diagnoses represents a significant leap forward in mental healthcare, ensuring individuals receive targeted and effective treatment rather than being dismissed with an outdated label.

3. The Evolution of Diagnoses: Beyond Hysteria

The journey from “hysteria” to contemporary psychological diagnoses marks a pivotal advancement in mental health. Today, medical professionals understand that the diverse symptoms once attributed to hysteria fall under several distinct categories of mental health conditions, primarily dissociative disorders and somatic symptom disorders. This reclassification has allowed for more accurate diagnosis, targeted treatment, and a destigmatization of these complex experiences.

Dissociative disorders involve disruptions in consciousness, memory, identity, emotion, perception, body representation, motor control, and behavior (Harvard, 2024). These conditions are often a psychological response to trauma, allowing individuals to mentally distance themselves from overwhelming experiences. Examples include dissociative amnesia, where personal information or specific events are forgotten; dissociative fugue, involving memory loss during a change in physical location, sometimes with the creation of a new identity; and dissociative identity disorder, characterized by the presence of two or more distinct personality states. The historical descriptions of trance-like states or sudden memory loss align closely with these modern understandings.

Somatic symptom disorder, another key diagnostic category, involves significant distress or functional impairment due to physical symptoms. Individuals with this disorder are preoccupied with bodily sensations like pain, weakness, or shortness of breath, causing substantial distress. It’s crucial to understand that they are not faking their illness; they genuinely believe they are unwell, even if medical tests find no clear physical cause. Conditions within this category include conversion disorder (functional neurological symptom disorder), where psychological distress converts into physical symptoms like paralysis or blindness; illness anxiety disorder (formerly hypochondriasis), characterized by excessive worry about having a serious illness; and factitious disorder (Munchausen syndrome imposed on oneself), where an individual consciously produces or feigns physical or psychological symptoms to assume the sick role.

The understanding that hysteria is not what it appeared to be—a singular, female-specific ailment—has revolutionized how we approach these conditions. By recognizing the intricate interplay between mind and body and acknowledging the profound impact of psychological trauma and stress, modern psychiatry offers pathways to healing that were unimaginable in the Victorian era. These precise classifications ensure that individuals receive comprehensive care tailored to their specific needs, moving far beyond the vague and often dismissive label of “hysteria.”

4. Understanding the Underlying Causes of Hysteria-Like Symptoms

The causes behind the symptoms once attributed to hysteria are now understood to be multifaceted, stemming from a complex interplay of psychological, social, and sometimes biological factors. Unlike the ancient focus on a “wandering uterus,” contemporary research pinpoints trauma and severe psychological stress as primary drivers for many dissociative and somatic symptom disorders (Harvard, 2024). This deeper insight confirms that hysteria is not what outdated theories suggested, but a manifestation of profound inner turmoil.

For dissociative disorders, the most common etiology is exposure to severe trauma. This can include experiences such as physical, sexual, or emotional abuse, especially during childhood. Natural disasters, combat exposure, and other life-threatening events can also trigger dissociative responses, where the mind creates a protective detachment from reality. This dissociation serves as a coping mechanism, allowing the individual to survive overwhelming situations by mentally compartmentalizing the traumatic memories or aspects of their identity.

Somatic symptom disorder often arises from a combination of factors, including adverse childhood experiences like abuse or neglect, genetic predispositions, and heightened anxiety about bodily processes. Individuals with a low pain threshold or a tendency to catastrophize minor physical sensations may be more susceptible. The disorder can be exacerbated by a lack of emotional expression, where psychological distress finds an outlet through physical symptoms. For instance, chronic stress from a demanding job or relationship issues might manifest as persistent, unexplained pain.

A fascinating aspect of hysteria’s historical context, and one that still holds relevance today, is the concept of hysterical contagion, now more broadly known as mass psychogenic illness or social contagion. This phenomenon occurs when symptoms, often associated with anxiety or stress, spread rapidly within a group of people, even without a physical or infectious cause. A historical example is the “dancing mania” of the Middle Ages, where groups of people would spontaneously begin dancing uncontrollably (Harvard, 2024). In a modern context, a group of students might experience unexplained headaches or nausea after a stressful exam, a manifestation of shared psychological distress. This collective response underscores how deeply intertwined our psychological states are with our physical experiences and social environments, reinforcing that the truth about hysteria is not what it appears on the surface, but a reflection of deeper psychological and social dynamics.

5. Contemporary Treatment Approaches for Related Conditions

For individuals experiencing symptoms once labeled “hysteria”—now understood as dissociative or somatic symptom disorders—effective treatment typically involves a comprehensive approach centered on psychotherapy. The goal is to address the underlying psychological distress, trauma, and maladaptive coping mechanisms that contribute to these conditions. Modern therapeutic interventions are highly specialized, offering hope and significant improvement for those affected.

One of the most widely used and effective treatments is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT). CBT helps individuals identify and challenge negative thought patterns and behaviors that perpetuate their symptoms. For somatic symptom disorder, CBT can help reframe catastrophic thoughts about physical sensations and develop healthier coping strategies for pain or discomfort. For dissociative disorders, it can assist in processing traumatic memories and integrating fragmented aspects of identity (Harvard, 2024).

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT), originally developed for borderline personality disorder, is also highly effective, particularly for individuals with severe emotional dysregulation and a history of trauma. DBT focuses on teaching mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness skills. These skills are invaluable for managing intense emotional outbursts and navigating complex relationships, which can be particularly challenging for those with dissociative experiences.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy is specifically designed to treat trauma-related conditions, including many dissociative disorders. EMDR helps individuals process distressing memories and reduce their emotional impact through guided eye movements or other bilateral stimulation. By reprocessing traumatic experiences, EMDR can alleviate symptoms like flashbacks, amnesia, and emotional numbness, which were historically linked to hysterical states.

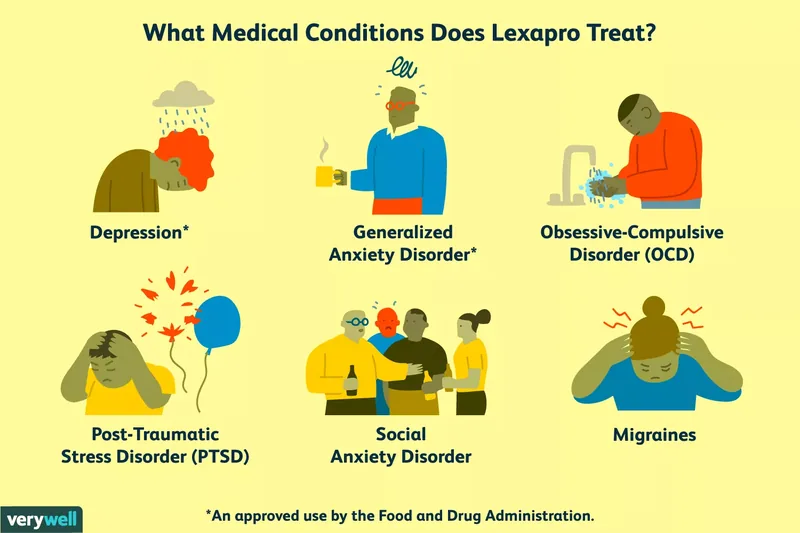

Mindfulness-based therapies, which emphasize present-moment awareness and non-judgmental acceptance, are also gaining traction. These approaches help individuals stay grounded, reduce anxiety, and improve their ability to observe thoughts and feelings without being overwhelmed by them. For someone experiencing derealization or depersonalization, mindfulness can be a powerful tool for reconnecting with their body and surroundings. In some cases, medication, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for co-occurring depression or anxiety, may be prescribed to help manage symptoms alongside therapy, recognizing that hysteria is not what can be cured by a single pill, but requires holistic care.

6. Empowering Coping Strategies for Mental Well-being

Living with symptoms once associated with hysteria, now recognized as dissociative or somatic symptom disorders, can be incredibly challenging. However, a range of empowering coping strategies, alongside professional support, can significantly improve daily functioning and overall well-being. These strategies focus on self-regulation, emotional processing, and fostering a sense of control over one’s internal experience.

One fundamental strategy is to practice mindfulness. This involves intentionally focusing on the present moment, observing thoughts, feelings, and sensations without judgment. For individuals prone to dissociative episodes or overwhelming physical symptoms, mindfulness can help ground them in reality, preventing rumination on past traumas or anxieties about the future. Simple mindfulness exercises, like focusing on the breath or engaging the five senses, can be powerful tools (Harvard, 2024).

Engaging in breathing exercises is another effective technique for managing anxiety and acute distress. Deep, diaphragmatic breathing activates the parasympathetic nervous system, promoting relaxation and reducing the physiological symptoms of stress. Techniques like the 4-7-8 breathing method can quickly calm an overactive nervous system, helping to mitigate emotional outbursts or the intensity of physical sensations.

Writing in a journal provides a safe and private outlet for processing emotions and experiences. By putting feelings, stressors, and symptoms onto paper, individuals can gain clarity, identify patterns, and release pent-up emotional energy. This practice can be particularly beneficial for those struggling with dissociative amnesia, helping to piece together fragmented memories or track symptom fluctuations over time. The act of externalizing internal struggles can be profoundly therapeutic.

Getting physically active is a well-documented booster for mental health. Regular exercise, whether it’s a walk, a hike, or a bike ride, releases endorphins, reduces stress hormones, and improves mood. Physical activity can also help individuals reconnect with their bodies, which is especially important for those who feel disconnected due to dissociative experiences or who are focused on distressing physical symptoms. It serves as a healthy distraction and a means of building resilience.

Finally, developing a consistent sleep schedule is crucial for mental and physical health. Sleep deprivation can exacerbate anxiety, heighten pain perception, and worsen dissociative symptoms. Prioritizing quality sleep by maintaining a regular bedtime and wake-up time, creating a relaxing bedtime routine, and optimizing the sleep environment can significantly improve an individual’s capacity to cope with their symptoms and manage their emotions effectively. Seeking the help of a mental health professional is always the first and most critical step, as these coping mechanisms work best when integrated into a comprehensive treatment plan that acknowledges hysteria is not what defines a person, but a historical term for treatable conditions.