In an age of constant information, understanding how scientific findings are communicated is more crucial than ever. Small scientific findings often become big stories because research conclusions are frequently reverse-engineered to fit appealing narratives, amplified by publication bias, motivated reasoning, and a public eager for simple answers. Even weak statistical effects can be presented as significant evidence when aligned with cultural concerns or moral panics, leading to exaggerated headlines and policy shifts. This dynamic, especially prevalent in 2025, distorts public understanding of complex issues and can lead to misinformed decisions.

This phenomenon matters because it impacts everything from public health policy to personal lifestyle choices. When negligible effects are portrayed as monumental, it can fuel moral panics, waste resources on ineffective interventions, and erode trust in science. For Routinova readers, understanding this distinction helps you navigate health trends, technology claims, and lifestyle advice with a more critical and informed perspective. It empowers you to discern genuine insights from overblown hype.

Understanding the 'Big Story' Phenomenon

The journey from a research idea to a headline-grabbing story is fraught with opportunities for exaggeration. At its core, the problem isn't necessarily poor research, but rather how conclusions are framed and communicated. Often, the way findings are presented seems reverse-engineered to fit a larger, more appealing narrative, leading to small effects becoming big stories. This dynamic is particularly potent in our current media landscape, where virality often trumps nuance.

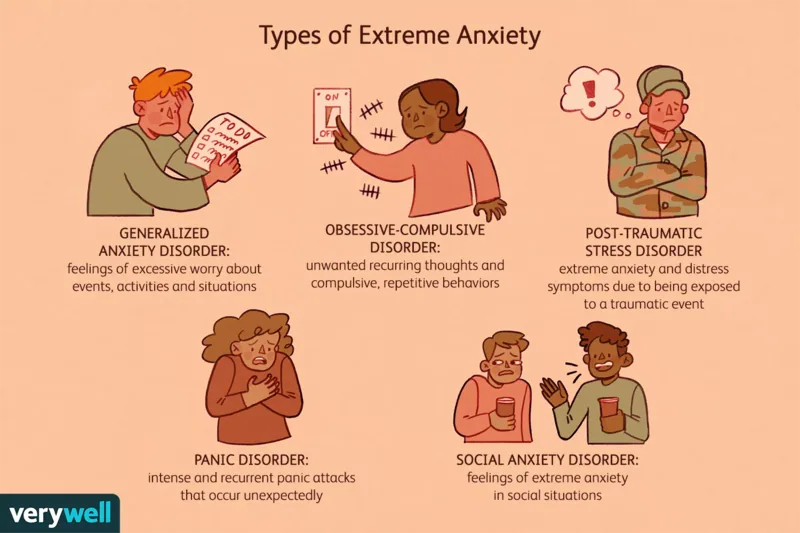

Consider seemingly disparate topics like the alleged dangers of certain "superfoods," the impact of extensive screen time on children, or the pervasive influence of AI in creative fields. All have recently been subjects of scientific claims, some modest, others quite dramatic, that rapidly escalated into widespread headlines. In each instance, the underlying research was used to construct a compelling story: 'miracle cures' for health issues, 'destroying a generation's mental health,' or 'AI silently replacing human creativity.' While these claims might contain a kernel of truth, many are significantly overblown, transforming minor findings into major headlines. This pattern highlights how weak effects can still influence public opinion and policy if the story resonates with existing beliefs or anxieties.

The issue isn't always that researchers are asking flawed questions or conducting subpar studies, though such instances do occur. Instead, the challenge lies in how conclusions are drawn and, more crucially, how they are communicated to the public. A statistically significant but weak result can easily be leveraged as "evidence" to support a narrative that is disproportionately exaggerated. The scientific methodology itself might be technically sound, yet the practical takeaway becomes unreasonable and misleading. This isn't a novel problem, but its visibility has dramatically increased with the rapid dissemination of information in 2025. Psychologist Christopher J. Ferguson (2025) has extensively argued that much of modern social science relies on weak effect sizes bolstered by strong convictions. With enough data, it often becomes possible to find some support for almost any hypothesis, especially when the goal is to create compelling big stories.

The Science of Amplification: Weak Effects, Strong Narratives

The transformation of minor scientific findings into major public narratives is a process influenced by several critical elements within research methodology itself. At the risk of oversimplification, three primary factors play a pivotal role in shaping study results and their subsequent interpretation. These elements are design, sample size, and analytics, and they each offer opportunities—conscious or unconscious—to nudge results toward a preferred interpretation, turning even subtle impacts into grand tales.

Study Design, Sample Size, and Analytics

First, the design of a study—detailing what variables are measured and precisely how—fundamentally dictates the inferences that can be drawn and the required sample size. A poorly designed study might inadvertently inflate perceived effects or limit the generalizability of its findings. Second, the sample size is crucial for determining whether an observed effect achieves "statistical significance." Paradoxically, with sufficiently large samples, even tiny effects that hold little practical meaning can appear statistically impressive on paper. This means a negligible effect could still clear the p < .05 threshold, making it seem noteworthy. Finally, analytics—the specific statistical methods applied—determine which patterns within the data are highlighted, which are downplayed, and how robust the results ultimately appear. These methods are integral to converting a complex, messy dataset into a clean, coherent, and often compelling story. Each of these components involves choices that are rarely neutral, and these choices can significantly alter the narrative the data tells, making even weak effects appear strong.

Statistical Significance vs. Practical Relevance

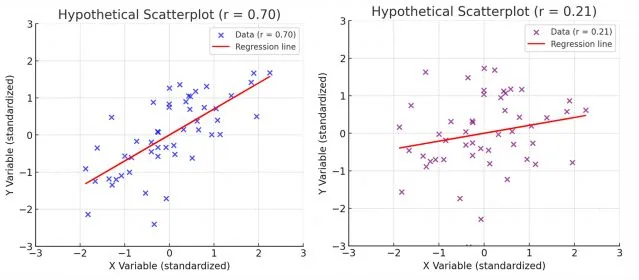

Once a result clears that "magical" p < .05 threshold, it becomes incredibly easy to overstate its importance, especially if the finding aligns with an intuitively appealing or morally charged narrative. This is precisely how weak effects can become sensational headlines, with nuance often getting overshadowed by moral panic. For instance, research on average effect sizes in pre-registered psychology studies (Schäfer & Schwarz, 2019) often reveals visually unimpressive trends. While statistically significant, such effects might show people at the low end of a scale looking remarkably similar to those at the high end, with considerable data noise. Yet, these subtle impacts can be dressed up as "proof" in public discourse, illustrating how small effects can become big stories even when practical relevance is minimal. This disconnect between statistical validity and real-world impact is a cornerstone of how minor findings can create major headlines.

Figure1 and 2. Two correlations with identical axis scaling.Source: OpenAI/ChatGPT

Real-World Impacts: When Minor Findings Create Major Headlines

The ability to dress up a small effect as "significant" makes it remarkably easy to weave it into a compelling narrative, which, in the world of research and public discourse, is a powerful currency. Compelling stories are more likely to be published, widely covered by the media, and acted upon by policymakers and the public. This dynamic is particularly evident when a result conveniently fits into an existing moral panic or cultural concern.

Consider the ongoing debate about screen time and its impact on mental health. A recent randomized controlled trial involving over 17,000 students tested whether removing phones from classrooms would improve academic performance (Sungu et al., 2025). The study did find a statistically significant improvement in grades—but the effect size was minuscule (d=0.086), equivalent to a correlation of about r=0.043. In practical terms, this impact is negligible. Furthermore, the researchers observed no significant changes in student well-being, academic motivation, online harassment, or overall digital use. Yet, it's easy to envision how a headline like "phone bans show tiny effects on grades" quickly transforms into "removing phones boosts performance," fueling policy debates and parental anxieties. The story resonates with existing societal concerns about technology and attention spans, and once framed this way, the small effect becomes a footnote rather than the focal point. This is a classic example of how weak effects, strong convictions can drive public perception.

This dynamic extends beyond technology. Think about the countless "superfood" trends or specific dietary supplements that gain immense traction. A study might show a statistically significant, but practically insignificant, reduction in a biomarker in a highly controlled lab setting. This minor finding is then amplified into dramatic claims of disease prevention or enhanced vitality, often without robust, large-scale human trials. For instance, a small study on the effect of a particular berry on antioxidant levels might lead to headlines proclaiming it a "cancer-fighting miracle," even if the actual biological impact is negligible (Harvard, 2024). These are powerful big stories built on a foundation of subtle impacts, often driven by commercial interests or a desire for quick solutions.

Decades of research into motivated reasoning further explain how these narratives take hold. People are more inclined to accept statistics and arguments that align with their existing beliefs or desired outcomes, while being far less critical of their weaknesses (Kunda, 1990; Taber & Lodge, 2006). The effects of motivated reasoning are often small to moderate in size (Ditto et al., 2019), meaning they aren't overwhelming, but they are strong enough to tilt judgments toward an appealing narrative. When a result "feels" true—when it perfectly fits the story we already believe—it becomes easier to overlook the actual smallness of the effect or to avoid scrutinizing it closely in the first place. At this point, small effects can pass as big ones not because the evidence is robust, but because it is convenient and confirms pre-existing biases. This is precisely how weak results, when paired with a receptive audience, can significantly drive policy, shape public opinion, and fuel widespread moral panics.

Navigating the Information Landscape in 2025

In the rapidly evolving digital ecosystem of 2025, the challenge of distinguishing between genuine scientific breakthroughs and overblown narratives is more pronounced than ever. We are constantly bombarded with information from diverse sources, making it imperative to develop robust strategies for critical consumption. The speed at which information, especially sensationalized content, propagates across social media platforms means that minor findings can create major headlines in a matter of hours, often without adequate scrutiny. This demands a proactive approach to how we engage with scientific claims and lifestyle advice.

One key aspect of navigating this landscape is recognizing the role of algorithms. Social media platforms and news aggregators are designed to show us content that aligns with our past interactions and perceived interests. This can inadvertently create echo chambers where narratives, even those based on weak effects, are reinforced and amplified, making it harder to encounter dissenting views or nuanced interpretations. Therefore, actively seeking out diverse sources and challenging our own confirmation biases becomes an essential skill. Furthermore, the rise of AI-generated content, while often sophisticated, can sometimes inadvertently perpetuate these overblown narratives by synthesizing information without fully grasping the nuances of effect sizes or practical relevance.

For Routinova readers, this translates into being an active, rather than passive, consumer of information. When encountering claims about health, wellness, or technology, especially those promising dramatic results or warning of dire consequences, pause and question the source and the underlying evidence. Understand that headlines are designed to grab attention, and often simplify or exaggerate complex scientific findings. The context in which research is presented is just as important as the research itself. In 2025, where information overload is the norm, cultivating a healthy skepticism and a commitment to seeking depth beyond the surface-level narrative is paramount. This proactive engagement helps in discerning genuine insights from the noise, protecting yourself from the allure of big stories that lack substantial evidence.

Pitfalls of Oversimplification: The Dangers of Uncritical Acceptance

The pervasive tendency to oversimplify complex scientific findings into easily digestible, often sensationalized, narratives carries significant risks. Uncritical acceptance of these big stories, especially when they stem from weak effects, can lead to a cascade of negative consequences for individuals and society alike. One of the most immediate dangers is the misallocation of resources and attention. When a negligible effect is presented as a crucial finding, it can divert funding, research efforts, and public focus away from truly impactful problems or more effective solutions. For instance, a highly publicized, yet scientifically weak, claim about a "detox diet" might lead countless individuals to spend money and effort on an ineffective regimen, neglecting proven health practices.

Beyond individual choices, oversimplification can distort public policy and perpetuate harmful stereotypes. Policies enacted based on exaggerated claims, even those with good intentions, can have unintended negative consequences. An example could be stringent regulations based on a minor correlation, which might stifle innovation or create unnecessary burdens without yielding significant benefits. Moreover, when small effects become big stories that align with existing biases or moral panics, they can reinforce societal prejudices. This happens when a weak correlation between a demographic group and a negative outcome is amplified into a sweeping generalization, fueling discrimination or stigmatization. The nuance of the original research, which might highlight multiple interacting factors or very limited applicability, is lost in the pursuit of a compelling, but ultimately misleading, narrative.

Another critical pitfall is the erosion of public trust in science itself. When the public repeatedly encounters sensationalized headlines that are later debunked or found to be based on flimsy evidence, it fosters cynicism. This can lead to a general distrust of scientific expertise, making it harder for genuinely important and robust findings to gain traction. In an era where scientific consensus is vital for addressing global challenges like climate change or public health crises, this erosion of trust is particularly dangerous. The constant need for researchers and communicators to produce "positive" or "exciting" results to secure funding or media attention can inadvertently contribute to this cycle of oversimplification and subsequent disillusionment. Therefore, understanding these dangers underscores the importance of scrutinizing claims, regardless of how appealing the big stories they tell might be.

Cultivating Critical Thinking: Your Guide to Smarter Consumption

In an environment where weak effects, strong convictions often shape public discourse, cultivating robust critical thinking skills is not just beneficial, but essential. For readers of Routinova, this means approaching lifestyle advice, health claims, and technological innovations with a discerning eye. The goal isn't to become a research scientist overnight, but to develop practical habits that help you differentiate between well-substantiated facts and exaggerated narratives. This empowers you to make informed decisions that genuinely benefit your well-being.

One foundational step is to always look beyond the headline. Headlines are designed to be catchy and often oversimplify. Instead, delve into the article's body to understand the actual findings. Ask yourself: What was the sample size of the study? Was it a diverse group, or was it limited? Was it an observational study, or a randomized controlled trial? The type of study design significantly impacts the conclusions that can be drawn. For instance, observational studies can show correlation, but not causation, a crucial distinction often blurred when small effects become big stories. Seeking this deeper context helps you evaluate the strength of the evidence presented.

Furthermore, pay close attention to effect sizes and practical relevance. If a study reports a "statistically significant" finding, but the effect size is minuscule (like the phone ban example with d=0.086), its practical impact might be negligible. A statistically significant result simply means an effect is unlikely due to chance, but it doesn't automatically mean it's important in the real world. Think about what the reported effect would actually mean for your daily life. Would a 0.043 correlation truly change your habits? (Harvard, 2024). Be wary of language that uses absolute terms like "proof" or "cure" based on a single study. Robust scientific conclusions typically emerge from multiple, independent studies with consistent findings. Applying this level of scrutiny to both results you intuitively like and those you initially distrust helps foster a balanced and informed perspective, ensuring that science genuinely informs your narratives rather than being bent to fit them.

Potatoes, smartphones, social media, and AI might not share much on the surface, but the way research about them has been packaged and received follows a strikingly familiar pattern. A small or highly specific finding gets distilled into a headline-friendly conclusion, often one that aligns perfectly with a pre-existing narrative. Once it fits that narrative, the actual effect size becomes secondary—or disappears entirely from public discussion. This cycle ensures that small effects become big stories, regardless of their true practical importance.

This is not an argument against studying these important topics. Good research questions sometimes yield small effects, and such results can still hold significant value, contributing to our overall understanding. However, when weak effects are presented as strong, definitive evidence—whether through selective framing, an appeal to moral urgency, or simply the gravitational pull of motivated reasoning—we risk inflating both their scientific and practical importance. The challenge lies in resisting the urge to overhype implications, diligently paying attention to effect sizes, and consistently distinguishing statistical significance from practical relevance. We must apply the same level of rigorous scrutiny to results we find appealing as to those we initially dislike. In the end, science is best served when it genuinely informs our narratives, rather than being contorted to fit them. Weak effects will always exist; our responsibility is to treat them for precisely what they are, and nothing more.