Lobotomy as mental health treatment represents one of psychiatry's most controversial chapters--a procedure that promised relief for severe psychiatric conditions but often delivered devastating, irreversible consequences. This surgical intervention, which involved severing connections in the brain's prefrontal cortex, was once celebrated as a medical breakthrough before its ethical and medical failures became undeniable.

Understanding Lobotomy

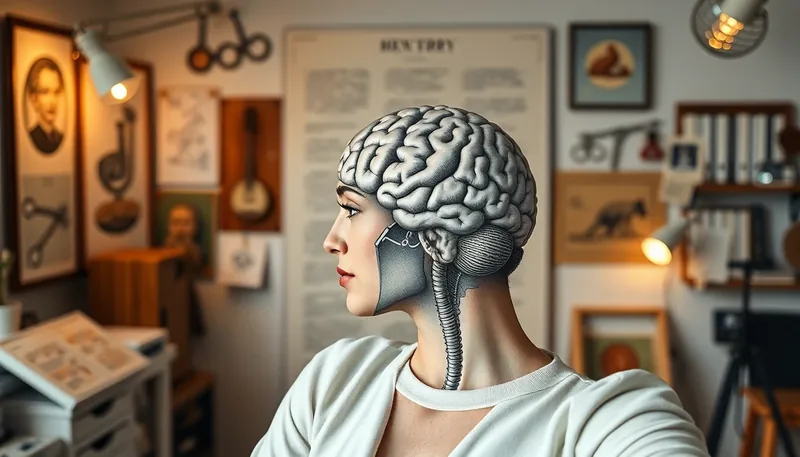

A lobotomy is a neurosurgical procedure designed to disconnect the prefrontal cortex from other brain regions. Developed in the 1930s, it aimed to treat severe mental health conditions by disrupting neural pathways believed to cause psychiatric symptoms. The theory suggested that severing these connections would calm agitation and reduce distressing thoughts, but the reality proved far more complex and damaging.

This approach to lobotomy as mental health intervention emerged during an era when psychiatric treatments were limited. Mental institutions overflowed with patients, and families desperate for solutions often turned to radical procedures. The promise of a quick "cure" overshadowed growing evidence of the procedure's destructive effects on personality, cognition, and basic functioning.

Historical Evolution

The Portuguese Origins

Portuguese neurologist António Egas Moniz performed the first lobotomy in 1935, initially injecting alcohol into the frontal cortex to destroy tissue. His "leucotomy" method evolved to use a specialized instrument called a leucotome to remove brain matter. Despite limited evidence of long-term success, Moniz received the 1949 Nobel Prize for this work--a decision that remains controversial in medical ethics discussions.

American Adaptation

Walter Freeman brought the procedure to the United States, initially collaborating with neurosurgeon James Watts. Dissatisfied with the complexity of existing methods, Freeman developed the transorbital "ice pick" lobotomy in 1946. This brutal modification involved hammering an instrument through the eye socket and manipulating it to sever brain connections, often performed without proper surgical facilities or anesthesia.

Freeman's streamlined approach allowed him to perform thousands of procedures across the country, promoting lobotomy as mental health solution for conditions ranging from schizophrenia to what he called "nervous indigestion." His traveling "lobotomy roadshow" demonstrated the procedure in state hospitals, contributing to its widespread adoption despite mounting evidence of harm.

Human Impact and Consequences

The effects of lobotomy varied dramatically between patients, but the most common outcomes were profoundly damaging. While some individuals experienced reduced agitation initially, most suffered permanent cognitive and emotional impairments. The procedure fundamentally altered personality, often leaving patients emotionally flat, cognitively impaired, and unable to function independently.

Common consequences included:

- Severe personality changes and emotional blunting

- Cognitive impairment affecting memory and reasoning

- Loss of initiative and motivation

- Physical complications including seizures and motor control issues

- In some cases, complete disability requiring lifelong institutional care

Medical literature from the period documents cases where patients lost the ability to perform basic self-care, recognize family members, or maintain employment. The very qualities that make us human--empathy, creativity, complex thought--were often sacrificed in pursuit of behavioral control.

Notable Cases and Personal Stories

Rosemary Kennedy

The most famous lobotomy patient, Rosemary Kennedy underwent the procedure at age 23 to control mood swings and behavioral issues. Her father arranged the surgery hoping to protect the family's political reputation. The operation left her permanently disabled, unable to speak coherently or care for herself, and institutionalized for the remaining five decades of her life.

Howard Dully

At just 12 years old, Howard Dully received a lobotomy from Walter Freeman after being labeled "difficult" by his stepmother. Dully spent decades in institutions before rebuilding his life. His 2005 memoir "My Lobotomy" brought renewed attention to the procedure's impact on children, highlighting how lobotomy as mental health treatment was applied to minors with devastating consequences.

Ellen Ionesco

A Romanian immigrant diagnosed with postpartum depression received a lobotomy in 1951. The procedure left her unable to care for her newborn child, with emotional responses so blunted that she showed no reaction to her baby's cries. Her case illustrates how the procedure affected women disproportionately, particularly those with conditions we now recognize as treatable with therapy and medication.

Frances Farmer

The Hollywood actress underwent multiple lobotomies during institutionalization for mental health struggles. While some accounts of her treatment have been disputed, her experience represents how public figures faced particular pressure to undergo radical treatments to maintain careers and public images, further complicating the ethics of lobotomy as mental health intervention.

Why Lobotomies Persisted

Despite growing evidence of harm, lobotomies gained popularity for several interconnected reasons. The mid-20th century offered few effective psychiatric treatments, creating desperation among families and institutions. Antipsychotic medications wouldn't emerge until the 1950s, leaving medical professionals with limited options for severe cases.

Institutional pressures played a significant role. Overcrowded mental hospitals sought ways to manage disruptive patients, and lobotomies offered a method to create more compliant, easier-to-manage individuals. The procedure's proponents, particularly Freeman, skillfully used media to promote lobotomies as modern miracles, while downplaying complications and ethical concerns (Harvard Medical School, 2023).

Economic factors also contributed. Lobotomies were relatively inexpensive compared to long-term institutional care, creating financial incentives for state hospitals. This combination of medical limitation, institutional need, and persuasive promotion created the conditions for lobotomy's temporary acceptance as legitimate mental health treatment.

Modern Perspective and Alternatives

Today, lobotomy is universally condemned as a barbaric chapter in psychiatric history. The development of effective psychotropic medications in the 1950s, particularly chlorpromazine, provided safer alternatives and contributed to the procedure's decline. Modern psychiatry emphasizes evidence-based treatments that preserve cognitive function and personal autonomy.

Current approaches to severe mental health conditions include:

- Psychotherapy modalities like cognitive-behavioral therapy and dialectical behavior therapy

- Medication management with antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers

- Brain stimulation techniques including electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and transcranial magnetic stimulation

- In rare, carefully regulated cases, precision neurosurgical interventions for treatment-resistant conditions

Contemporary psychosurgery differs fundamentally from historical lobotomy. Procedures like deep brain stimulation use implanted electrodes to modulate specific brain circuits without destroying tissue. These interventions undergo rigorous ethical review and require exhaustive documentation of treatment resistance before consideration (Mayo Clinic, 2024).

Ethical Legacy and Lessons

The history of lobotomy as mental health treatment offers crucial lessons about medical ethics, patient autonomy, and the dangers of therapeutic enthusiasm. It highlights the importance of rigorous scientific evaluation before adopting new treatments, particularly those with irreversible consequences. The procedure's popularity despite limited evidence serves as a cautionary tale about the influence of charismatic proponents and media hype in medicine.

Modern psychiatric ethics emphasize informed consent, patient autonomy, and the precautionary principle--especially for interventions affecting personality and cognition. The lobotomy era's failures contributed to developing contemporary research ethics, including institutional review boards and requirements for controlled clinical trials before treatment adoption.

This historical chapter also reminds us of the importance of humility in medicine. What seems like a breakthrough today may be viewed as barbaric tomorrow. The evolution from lobotomy to modern mental healthcare demonstrates psychiatry's progress toward treatments that heal rather than harm, that respect human dignity while addressing suffering--a fundamental shift in how we approach lobotomy as mental health history and its painful legacy.