It’s natural to seek a straightforward explanation for why mental health conditions emerge. However, the truth is far more intricate than any single factor can explain. Mental well-being is a complex interplay of various elements, making a simple, singular cause elusive. This complexity presents a significant challenge in both understanding and addressing mental health concerns effectively.

For decades, researchers have grappled with the question of why some individuals develop mental health disorders while others, exposed to similar stressors, do not. The answer often lies not in a single genetic flaw or a traumatic event alone, but in a dynamic interaction between our inherent biological makeup and the pressures of life. This is precisely about the diathesis-stress model, a foundational theory that offers a comprehensive framework for understanding this intricate relationship. It posits that mental health conditions arise from a combination of an individual’s predisposition (diathesis) and their exposure to environmental or psychological stress. This model helps explain the variability in human responses to adversity and is crucial for developing personalized approaches to mental health in 2025 and beyond.

1. Why Single-Cause Explanations Fall Short

For a long time, discussions around mental health often leaned towards either a purely “nature” (genetics) or “nurture” (environment) perspective. Early theories sometimes oversimplified mental illness, attributing it solely to biological imbalances or, conversely, to adverse life experiences. However, these singular explanations frequently failed to account for the full spectrum of observed outcomes. For instance, if mental disorders were purely genetic, identical twins would always share the same conditions, which isn’t the case. Similarly, if trauma alone caused disorders, everyone exposed to significant stress would develop a condition, which is also untrue. These limitations highlighted a critical gap in understanding.

The inadequacy of single-cause explanations became increasingly evident as research progressed. It became clear that a more nuanced framework was needed to explain why some individuals are more resilient to stress than others, or why a genetic predisposition might lie dormant in one person but manifest dramatically in another. This challenge spurred the development of integrative models, paving the way for a theory that could account for the complex interplay of factors. The recognition that neither genes nor environment act in isolation, but rather in concert, was a pivotal shift in psychiatric thought. Without this comprehensive view, treatment approaches could be incomplete, focusing only on symptoms or isolated risk factors rather than the holistic picture. This fundamental problem ultimately underscores the necessity of frameworks like the diathesis-stress model, which acknowledges the multi-faceted origins of mental health conditions.

2. Understanding Diathesis and Stress

At its core, the diathesis-stress model offers a powerful lens through which to view mental health. While the terminology might seem academic, the concepts are highly relatable. The model proposes that mental health challenges, and indeed many medical conditions, arise from the interaction of two main components: diathesis and stress. This dual perspective is fundamental to grasping about the diathesis-stress model.

Diathesis refers to an individual’s inherent vulnerability or predisposition to developing a particular mental disorder. This predisposition isn’t a guarantee of illness but rather an increased susceptibility. Diathesis can manifest in various forms, including genetic factors, such as inheriting specific gene variants that influence brain chemistry or structure. It can also stem from early life experiences, like developmental trauma or adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which can alter brain development and psychological resilience. Biological susceptibilities, such as neurotransmitter imbalances or certain personality traits, also fall under the umbrella of diathesis. Understanding an individual’s diathesis is key to identifying who might be at higher risk.

Stress, in the context of this model, encompasses the environmental or psychological factors that can trigger the onset of mental illness or exacerbate existing conditions. These stressors are not merely everyday annoyances but can range from significant life events like job loss, relationship breakdowns, or bereavement, to more acute forms of trauma such as abuse or accidents. Daily stressors, even seemingly minor ones, can accumulate over time and contribute to the overall stress load. The crucial insight here is that stress interacts with diathesis; a person with a high diathesis might develop a disorder in response to a moderate stressor, whereas someone with a low diathesis might withstand even severe stress without developing the same condition. This interaction is central to explaining why individuals respond so differently to life’s challenges.

3. The Evolution of the Diathesis-Stress Model

The conceptual roots of the diathesis-stress model stretch back to earlier ideas about predisposing and exciting causes of illness, even in the 19th century. However, its formal application to mental health began to take shape in the mid-20th century. A significant milestone in the development of about the diathesis-stress model was in the 1960s when psychologist Paul Meehl applied this framework specifically to explain the origins of schizophrenia. Meehl proposed that individuals with a genetic predisposition (diathesis) for schizophrenia would only develop the disorder if exposed to sufficient environmental stress. This was a revolutionary idea at the time, moving beyond purely biological or purely environmental explanations.

Following Meehl’s groundbreaking work, the model’s utility quickly expanded beyond schizophrenia. Researchers began to apply the vulnerability-stress model to understand other complex mental health conditions, including major depressive disorder. Studies suggested that individuals with a genetic or biological vulnerability to depression were far more likely to experience a depressive episode when confronted with significant life stressors, such as financial difficulties, relationship conflicts, or personal loss (Harvard, 2024). This broader application demonstrated the model’s versatility and its ability to provide a consistent explanation for the heterogeneous nature of mental illness.

By the early 21st century, the diathesis-stress framework had become one of the most widely accepted and influential theories in psychopathology. It was further refined to include a wider array of conditions, such as anxiety disorders, eating disorders, and even substance use disorders. The model continues to evolve, with emerging research in 2025 and beyond exploring the specific genetic markers, neurological pathways, and psychological mechanisms that constitute diathesis, as well as the diverse types of stressors and their cumulative impact. This ongoing research solidifies the model’s importance in guiding both theoretical understanding and practical interventions in mental health.

4. How the Diathesis-Stress Model Works in Practice

The practical application of the diathesis-stress model offers a profound understanding of individual differences in mental health outcomes. Everyone possesses a unique set of vulnerabilities, whether inherited through genes, acquired through early developmental experiences, or resulting from complex gene-environment interactions. However, merely having these predispositions does not automatically lead to the development of a mental disorder. The model distinctly highlights that a disorder typically only manifests when these underlying vulnerabilities are activated by stress-related pressures. This interactive dynamic is critical when learning about the diathesis-stress model.

Consider an individual with a genetic predisposition for anxiety (a diathesis). They might navigate life without developing an anxiety disorder if their environment is relatively stable and supportive. However, if they encounter a period of intense, prolonged stress—such as a demanding job, a major life transition, or a traumatic event—this stress can act as a trigger, causing the latent vulnerability to express itself as clinical anxiety. The stress doesn’t cause the anxiety in isolation, but rather it interacts with the existing diathesis to push the individual past their coping threshold. Conversely, someone without a significant diathesis might experience similar stressors without developing a disorder, showcasing their inherent resilience.

The heritability of mental illnesses varies significantly, ranging from approximately 40% for depression to around 80% for schizophrenia, indicating a strong genetic component (Harvard, 2024). However, it is crucial to remember that very few mental disorders are caused by a single gene. Instead, it is usually the result of multiple genes interacting with each other and with various environmental factors. This complex interplay determines an individual’s overall risk and explains why the diathesis-stress model is so vital: it moves beyond simplistic cause-and-effect to a more dynamic, interactive understanding. For professionals and individuals alike, understanding this mechanism allows for targeted interventions that either reduce diathesis (where possible, e.g., through early intervention) or, more commonly, mitigate the impact of stress.

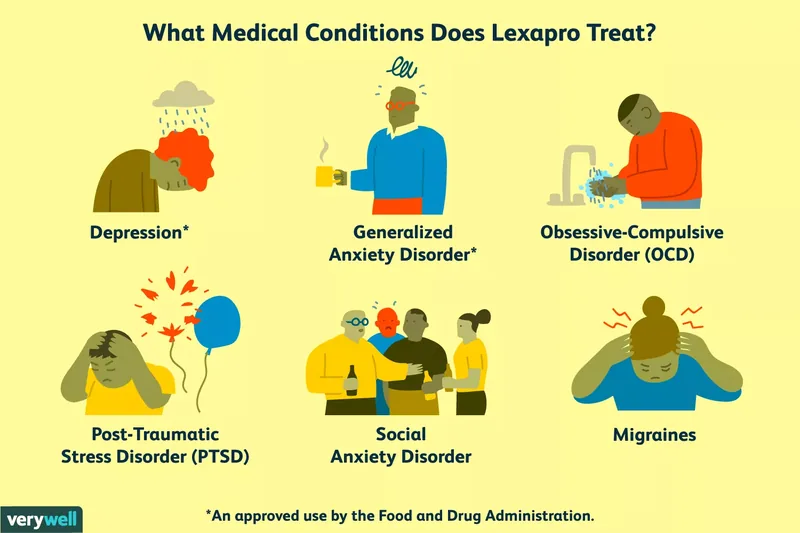

5. Common Conditions Illuminated by the Model

The diathesis-stress model has proven instrumental in shedding light on the complex origins of a wide array of mental health conditions. Its explanatory power extends to some of the most prevalent disorders in society, demonstrating that a combination of genetic vulnerabilities and environmental stressors is a common thread. Understanding about the diathesis-stress model in relation to specific conditions allows for more targeted prevention and treatment strategies, especially as we look towards enhanced mental health support in 2025.

Anxiety Disorders: While the precise mechanisms of anxiety disorders are still being unraveled, the diathesis-stress framework provides a robust explanation. Research indicates that anxiety disorders often have a familial component, suggesting genetic vulnerabilities. Individuals inheriting this predisposition may have a nervous system that is more sensitive to perceived threats or a lower threshold for stress. When such an individual encounters significant stressors—be it chronic work pressure, relationship issues, or traumatic experiences—their inherent vulnerability makes them more susceptible to developing clinical anxiety. Genetics can also influence how an individual processes and manages stress, further impacting their risk profile.

Depression: The onset of depression is widely understood through the lens of the diathesis-stress model. Individuals with a family history of depression are often considered to have a genetic diathesis. This vulnerability means they are more likely to experience a depressive episode when confronted with prolonged or severe stress. Stressors such as financial instability, bereavement, or chronic illness can trigger biological and psychological responses that overwhelm a predisposed individual’s coping capacity. When these life events exceed an individual’s ability to effectively manage them, particularly in the presence of a vulnerability, it significantly increases the likelihood of developing clinical depression.

Schizophrenia: This severe mental disorder is a classic example where the diathesis-stress model offers profound insights. While a strong genetic component is undeniable—for instance, individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome have a significantly elevated risk—not everyone with this genetic variation develops schizophrenia. This crucial observation points to the necessity of environmental factors. Stressors such as prenatal complications, childhood trauma, or significant life transitions in adolescence or early adulthood can act as triggers, interacting with the underlying genetic diathesis to precipitate the disorder’s onset. The model helps explain why some genetically vulnerable individuals remain unaffected while others develop the condition.

Eating Disorders: The development of eating disorders like anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa is also intricately linked to genetic, environmental, and psychosocial factors. Individuals may possess an inherent vulnerability, perhaps related to personality traits like perfectionism or body image concerns. When these predispositions combine with significant life stressors, such as societal pressures regarding appearance, critical comments, or experiences that lead to a profound sense of loss of control, a vulnerable individual might resort to extreme behaviors concerning food intake and weight as a coping mechanism. The model highlights how stress can activate underlying psychological and biological susceptibilities, leading to the manifestation of these complex disorders.

6. Applying the Diathesis-Stress Framework for Well-being

The profound implications of the diathesis-stress model extend far beyond theoretical understanding; it actively shapes research, diagnosis, and treatment strategies for mental disorders. By providing a holistic lens, this framework has revolutionized how we approach mental health, moving towards more integrated and effective interventions as we progress into 2025. The practical applications of learning about the diathesis-stress model are invaluable for both clinicians and individuals seeking to foster mental well-being.

One of the primary uses of the diathesis-stress model is its ability to enhance our understanding of the multi-faceted causes of mental illness. Unlike older models that focused exclusively on either biological (nature) or environmental (nurture) factors, this framework champions an integrative perspective. It asserts that mental disorders are best understood as the complex outcome of both biological predispositions and environmental influences interacting. This nuanced view allows researchers to design more sophisticated studies, exploring the intricate pathways through which genes, early experiences, and current stressors converge to impact mental health. This comprehensive understanding is crucial for moving beyond symptomatic treatment to addressing root causes and vulnerabilities.

Furthermore, the model underscores the importance of reducing stress as a modifiable risk factor for mental disorders. While genetic and other biological predispositions are largely immutable, stress is something individuals can actively manage and mitigate. This emphasis has directly influenced the development and widespread adoption of stress reduction strategies. Lifestyle changes, such as adopting regular exercise routines, practicing mindfulness, and cultivating strong social support networks, are now recognized as essential tools not just for general well-being, but specifically for reducing the risk of mental illness in predisposed individuals. This proactive approach empowers individuals to take charge of their mental health by addressing the environmental triggers that can activate their diathesis.

The diathesis-stress model also plays a crucial role in guiding research into the complex interactions of biological and environmental influences. It helps scientists identify specific genetic markers that confer vulnerability, investigate how early life experiences can ‘program’ stress responses, and understand how different types of stressors impact individuals based on their unique predispositions. This directed research is continuously leading to the discovery of more effective, personalized treatments. For example, understanding how certain genetic variations influence an individual’s response to psychotherapy or medication can lead to more tailored therapeutic approaches, enhancing treatment efficacy. As research evolves in 2025, the model continues to be a cornerstone for unraveling the intricate tapestry of mental health.

7. Proactive Strategies for Stress Management

While eliminating all sources of stress from life is an unrealistic goal, effectively managing and mitigating its impact is profoundly achievable. Developing robust stress management skills can significantly lower your health risks, particularly if you have an underlying diathesis. The insights gained about the diathesis-stress model empower us to prioritize stress reduction as a cornerstone of mental well-being. Proactive engagement with stress management is a powerful solution to protect your mental health, even in the face of vulnerabilities.

One of the most crucial initial steps is to identify your personal sources of stress. This involves self-reflection to pinpoint what situations, relationships, or internal thoughts consistently trigger feelings of overwhelm or anxiety. Understanding what is stressing you out, and why, is the foundation for effective management. For instance, is it work pressure, financial worries, or relationship conflicts? Once identified, you can then explore ways to avoid or minimize your exposure to these stressors where possible. This might involve setting boundaries, delegating tasks, or making lifestyle adjustments to reduce chronic demands. While not all stressors can be eliminated, strategic avoidance or reduction can significantly lighten your overall stress load.

Developing healthy coping mechanisms is another vital component. Instead of relying on maladaptive strategies like excessive consumption or avoidance, cultivate positive habits such as self-care routines, engaging in hobbies, or practicing problem-solving techniques. These skills equip you to navigate challenging situations constructively. Integrating relaxation strategies into your daily routine is also highly effective. Techniques like deep breathing exercises, progressive muscle relaxation, or guided meditation can activate your body’s relaxation response, counteracting the physiological effects of stress. Regular practice can build resilience over time (Harvard, 2024).

Furthermore, regular physical activity has been consistently shown to be a powerful stress reducer. Exercise releases endorphins, which have mood-boosting effects, and can also serve as a healthy outlet for pent-up tension. Even moderate activity, such as a daily walk, can make a significant difference. Lastly, cultivating gratitude through practices like writing in a gratitude journal can shift your perspective. Focusing on positive aspects of your life can enhance your emotional resilience and improve your ability to cope with ongoing stressors. These protective factors, including secure attachments, positive relationships, and strong emotional competence, act as buffers, strengthening your ability to manage the interaction between diathesis and stress. By proactively implementing these strategies, individuals can significantly fortify their mental health against both inherent vulnerabilities and life’s inevitable pressures.

8. Frequently Asked Questions about the Diathesis-Stress Model

Here are some common questions to further clarify about the diathesis-stress model and its implications for mental health.

What is the core idea of the diathesis-stress model? The core idea is that mental health problems are not caused by a single factor, but rather by the interaction between an individual’s pre-existing vulnerability (diathesis) and environmental or psychological stressors. It’s a combination of “nature” and “nurture.”

Can I change my diathesis? While genetic predispositions (part of diathesis) are largely fixed, some aspects of diathesis, such as vulnerabilities developed from early life experiences, might be mitigated through therapy or supportive environments. More commonly, the focus is on managing stress and building protective factors.

Does everyone with a diathesis develop a mental disorder? No, not everyone with a diathesis will develop a mental disorder. The model emphasizes that a disorder typically only emerges when a sufficient level of stress interacts with the existing vulnerability. Without adequate stress, the diathesis may remain latent.

How does the model influence mental health treatment? The model encourages treatment approaches that not only address symptoms but also aim to reduce stress and build coping skills. This includes therapies focused on stress management, resilience-building, and sometimes early interventions to mitigate developmental vulnerabilities.